Alternative text (“alt text”) was first introduced in the 1990s to compensate for the slow loading time of online images.[1] It formed part of the HTML code that allowed a textual description of an image to replace the visual if the image could not be displayed. Today, this term is commonly used to refer to image descriptions for blind and low-vision individuals.[2] These image descriptions can be accessed by screen readers, which read aloud digital media such as websites, documents, software, and the content found therein.

Alt text has been of recent interest to Artexte as it pertains not only to our social media presence—which includes alt text for images—but also to our ongoing accessibility project, which aims to make documents in our collection more accessible to all users through digitization and remediation. These processes involve creating high-quality scans of physical documents, which are processed through optical character recognition (OCR) to make the text searchable and readable by the computer. Alternative texts are then written to describe the images, which may include photographs, illustrations, reproductions of artworks, charts, diagrams, and more. Finally, these documents are made available to researchers through our digital repository at www.e-artexte.ca. As the Information Services Assistant for Artexte, I am tasked with implementing this procedure and developing an internal guide for writing image descriptions in the context of the visual arts. Given that art is something that often eludes words and involves a great deal of interpretation, writing such a guide and implementing it in the accessibility project has required much research and reflection. I am excited to share the results of this learning experience as well as my hopes for the future of alt text in the visual arts.

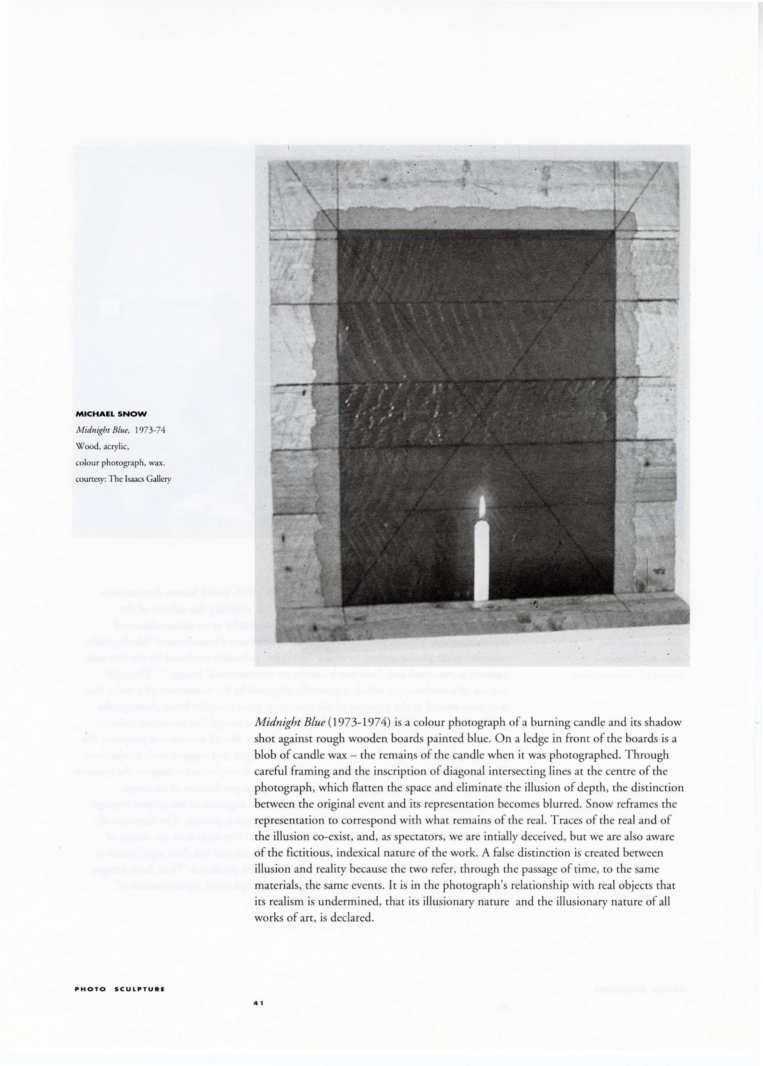

It can be intimidating to begin writing alt text for the first time: it certainly felt daunting when I started and I still struggle with balancing brevity, accuracy, and relevance in my descriptions. In spite of this, it feels like something of a self-fulfilling prophecy to open this discussion by framing it as “why writing alt text is difficult.” I fear that if I overemphasize the challenges associated with the process of writing good and useful alt text, I could deter people from ever trying to write it at all. As with any form of writing, however, writing alt text only gets better with practice. Indeed, although this is not always easy—especially for beginners—it is true of any skill that is under development. There is also the fear of not doing an image justice or not writing a description “properly.” I take comfort, however, in knowing that capturing the visual in words is not such a novel concept in the realm of the fine arts. Before high-quality colour image printing became more affordable, textual descriptions of artworks supplied by curators and critics were more heavily relied on than images. This practice persists today—typically in small publications—in spite of a shift towards privileging images in recent years. By developing our ability to describe images, then, we not only hone our eye but also continue to practice skills and techniques that have been developed as part of the study of art. An example of this can be seen in this excerpt from a 1991 exhibition catalogue that I have recently processed:

Midnight Blue (1973–1974) is a colour photograph of a burning candle and its shadow shot against rough wooden boards painted blue. On a ledge in front of the boards is a blob of candle wax—the remains of the candle when it was photographed. Through careful framing and the inscription of diagonal intersecting lines at the centre of the photograph, which flatten the space and eliminate the illusion of depth, the distinction between the original event and its representation becomes blurred.

I can only marvel at the amount of concise detail the author employs here, which effectively produces imagery that is both vivid and beautiful. Many essential descriptive elements are present, including colour, texture, and composition. It’s almost as if the author has followed a guide for writing alt text. In fact, although this description is accompanied by a black-and-white reproduction of the work, I find that the description allows for better comprehension of its physical configuration and colour than the image itself. Describing images of art feels a lot more approachable when you take into consideration that well-established methods of visual analysis already exist that require only minimal modification to become true alt text.

Another challenge in writing alt text is striking a balance in how we approach objectivity. The standard recommendation in alt text guides is that the alt text author should take an objective role so as to not insert their own interpretations and biases into the descriptions.[4] This presumed neutrality, however, which is reinforced by the impersonal, uncredited mode in which alt text is presented[5], does not take into consideration the fundamentally interpretive nature of writing image descriptions. This is complicated further by the level of interpretation that artworks often require, especially when dealing with a high degree of abstraction. Authors of alt text in the visual arts must toe an especially thin line between leading their readers to a certain interpretation and being unable to describe the image before them at all. We should, of course, recognize our inherent biases and actively attempt to counteract their ill effects. One common example of such biases is the tendency for alt text authors to presume whiteness as a default—for example, describing the skin tones of non-white people represented in an artwork while omitting any mention of skin tone for white people.[6] Although balancing objectivity, accuracy, and usefulness is a delicate procedure, clear guidelines that minimize the impact of systemic biases but still allow for flexibility in creative expression can help authors determine the best procedure for describing a given image.

An exciting prospect for expressing creativity in image descriptions is proposed in the Alt-Text as Poetry project by Bojana Coklyat and Finnegan Shannon[7], which challenges us to expand our notions of what alt text can be and do. Coklyat and Shannon are proponents of the movement to shift the perception of alt text from a merely “perfunctory” task into one that marries beauty, exploration, and competence through the use of poetic language.[8] More a guiding philosophy than a rulebook, Alt-Text as Poetry demonstrates how alt text presents an opportunity for individuals and institutions to incorporate the practice of care in their work. By taking the time to make our image descriptions accessible and enticing, we create a welcoming space for everyone in our community. It’s not that every image description has to be perfectly melodious and clever, refined to evoke the most intense imagery. After all, the ultimate goal is to produce an accessible document and sometimes “plain and simple” is the most effective method of communication. However, following the Alt-Text as Poetry approach allows us to be more purposeful and reflective in our descriptions—and makes the process more fun for both the alt text creator and the alt text reader.

Ultimately, my hope is that by becoming aware of the importance of alt text and having the most intimidating aspects of the process demystified for them, more artists and art organizations will feel encouraged to integrate image descriptions into their regular activities. Artists are ideally positioned to write high-quality alt text about their own work as they are the ones most familiar with its content and intentions. This means they can encode into their image descriptions textually a comparable meaning to what they encoded into their artwork visually.[9] If artists are given the tools to write alt text and supported by institutions in doing so, then accessibility practices could more easily be incorporated into everyday creative practice. Situated as it is at the intersection of artistic production and art documentation, and as a point of connection for people and institutions in the art community, the Artexte team aspires to contribute to this goal through our commitment to provide equitable access to our spaces and resources.[10] To this end, Artexte welcomes comments and suggestions on our accessibility offerings. Please write to us at accessibilite@artexte.ca.