For me, as a neurodivergent artist, creating Classroom of Language was about more than merely curating an exhibition. As it unfolded, the show became a profound exploration of inclusivity within language. This endeavour was focused not only on showcasing my art but also on fostering meaningful dialogue with visitors, allowing me to delve further into perceptual themes. Reading the introduction in the exhibition booklet, I found resonance in Mojeanne Behzadi’s words, seeing them as a scan of myself. Through the project, situated within the broader context of my residency at Artexte, I gained insights into the nature of communication and its accessibility, found solace in the act of creation, and underwent therapeutic self-discovery.

A stimulating investigation of perception, Classroom of Language prompts us to embrace cognitive diversity. Through my creations and conceptual approach, I encourage the public to reconsider the implications of the conveyance methods that we use to shape our understanding of the world and our place within it. The exhibition also questions the consequences of our increasingly online interactions and the impact of digital technology on expression and connectivity. It serves as a space in which we may reflect on the importance of in-person presence in nurturing authentic connections and for advancing the boundaries of language in pursuit of a more interconnected and empathetic society.

One of the exhibition’s most rewarding aspects was the sensorial visits, which were characterized by genuine involvement and enthusiasm on the part of the attendees, who interacted with the artworks using various sensory stimulation techniques. This provided insightful reflections and sparked conversations regarding disparities in communication accessibility. During the guided tours, I had the pleasure to connect with guests alongside artist Claudette Lemay as well as Kaysie Hawke and Manon Tourigny from Artexte. This collaborative effort aimed to nurture creativity, introspection, and dialogue within the setting of the installation.

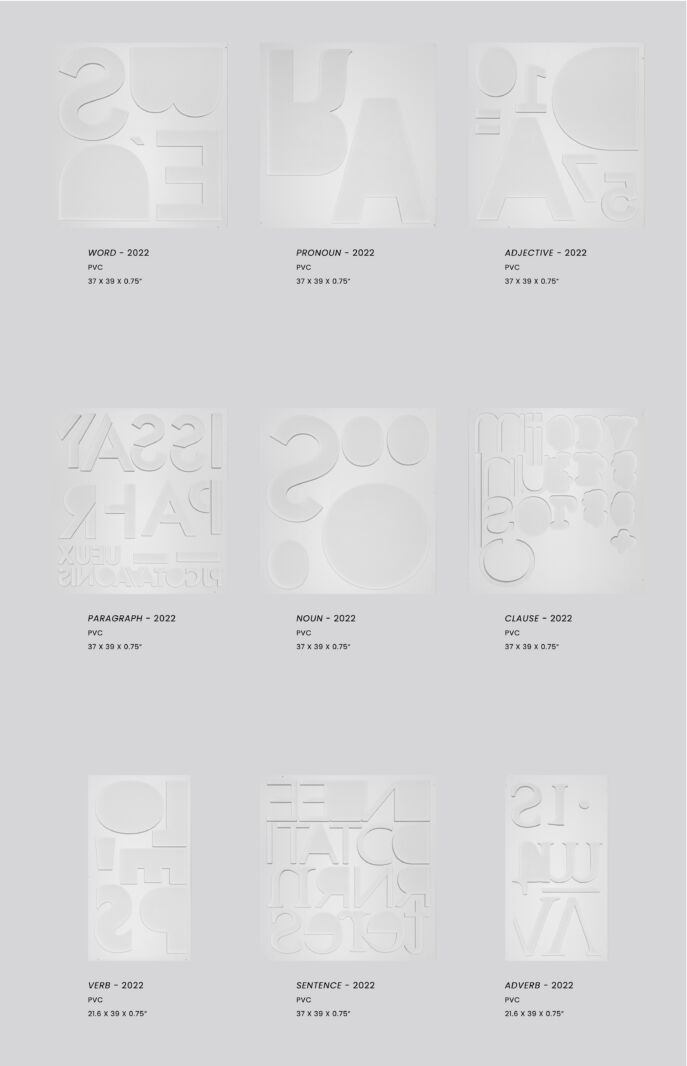

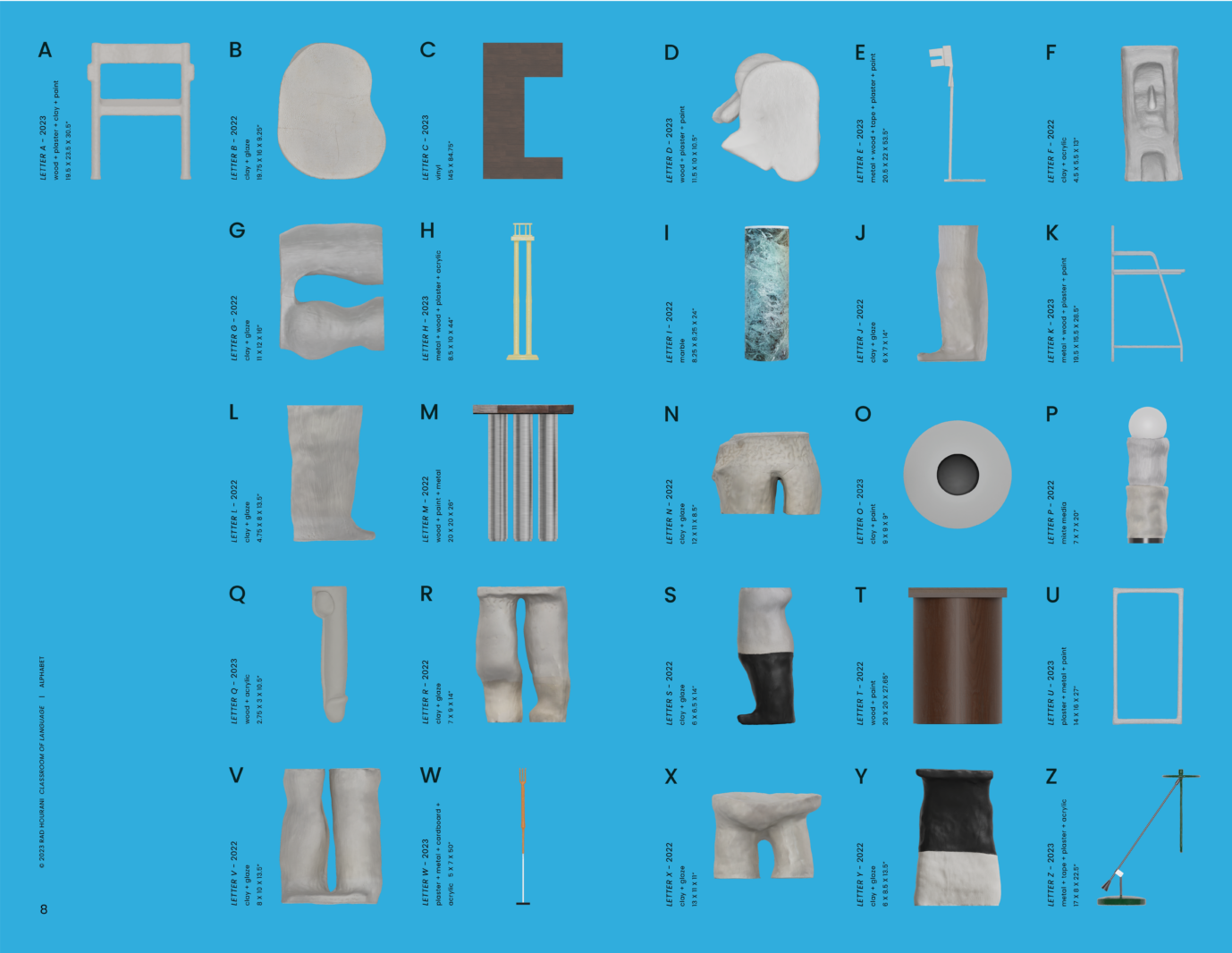

Remarkable insights were shared during a sensorial visit reserved for individuals who are blind or have low vision. One guest, despite having lost their sight at a young age and, as a consequence, having seen no alphabetical characters for many years, identified all the letters inscribed on the WRITING SYSTEMS (2022) artworks exclusively by touch, irrespective of the individual letter’s rotations or missing parts. Another guest, also blind, discerned a variety of materials used in the ALPHABET (2023) series as well as the distance between sculptures, solely by sound. These realizations underscored for me the distinctive skills of people with visual impairments.

In contrast, insights from sensory tours open to all attendees emphasized the differences between encounters involving individuals with visual impairments and those without. Among sighted participants, who routinely use identical alphabet characters and perceive materials visually in daily life, many were surprised to discover their inability to discern the letters engraved on the artworks through touch and struggled to recognize the substances utilized in the sculptures and their configurations. However, the experience ignited the guests’ imaginations in unexpected ways as they perceived fantastic landscapes and forms through their fingertips.

Participants navigating and interpreting the installation through tactile and auditory means identified the significance of sensory perception and the multifaceted ways in which we engage with art and communicate with one another. The potency of these encounters with sound and material empowered visitors to attain a deeper grasp of the exhibition’s themes and pieces. These firsthand accounts emphasized the value of building welcoming, accessible spaces within the realm of the arts. By providing avenues for stimulating our imaginations and exploring language in a multisensory way, installations like Classroom of Language ensure that people with varied capabilities can participate actively and interact with the displayed artworks. This may prompt us to consider how we might not be utilizing all of our senses to their utmost extent. Just as visually impaired individuals learn to rely on their senses of touch, hearing, and smell, we may allow ourselves to be reminded that each of us holds within ourselves untapped potential, challenging us to delve into our sensory experiences and transcend the confines of sight.

These insights underscore the transformative capacity of art to cultivate connection, understanding, and appreciation across diverse abilities or backgrounds. By adopting a more comprehensive approach to art and discourse, we can establish environments where all individuals feel a sense of belonging. This aligns with the ethos of the Classroom of Language exhibition, which aimed to question conventional norms of communication.

I intend to continue to explore the intersections of language and inclusivity in my artistic endeavours. Through ongoing collaboration and dialogue, I aspire to further amplify the voices of marginalized communities and advocate for constructive change in terms of how we express ourselves and connect with one another. By challenging established linguistic standards and embracing alternative modes of expression, we can create a more equitable society within which everyone has a voice.

Reflecting further on the project, I contemplate the concept of innate communication—free from programmed or acquired vocabulary—that resonates with the inherent modes of expression found in other species. This form of communication encompasses our inborn potential for conveying and interpreting meaning through sensory experiences, transcending memorized linguistic frameworks. Non-verbal cues such as gesture, facial expression, body language, and rhythm combine to weave a rich tapestry of human connection. I wonder if these aspects of interaction are ingrained in our biology and perceptual encounters, akin to how animals in their habits communicate via sound, scent, and movement.

Central to my inquiry is the concept of biocommunication, the exchange of information between living organisms. Drawing inspiration from natural signalling systems, I rethink our dependence on complex linguistic structures in favour of a more embodied language rooted in our biological sensory encounters. Witnessing non-human communication methods in nature, such as mammal vocalizations or the waggle dance performed by honey bees, grants us insights into sustainable communicative tools that prioritize our sensorial stimulation. For example, the honey bee waggle dance serves as a method of relaying details about the location of food sources to other hive members. Through intricate movement and vibration, bees communicate the direction, distance, and quality of the nourishment source, enabling their colony to gather resources efficiently while conserving energy. This natural system of conveying complex data illustrates an effective and enduring approach within a social community, highlighting the interconnectedness and symbiotic harmony of all organisms within an ecosystem.

Additionally, by exploring memory recording systems, we can further enrich our comprehension of human communication. In my interdisciplinary practice, I delve into these concepts by integrating various stimuli into my work, including visual imagery, tactile materials, and audio recordings, in the aim of eliciting personal recollections and responses of the audience. Through immersive experiences, my approach encourages individuals to observe their perceptions at a deeper level, nurturing a sense of cohesion and solidarity. This method not only surpasses the constraints of verbal language but also fosters experiential knowledge by appealing to diverse sensory modalities, allowing for a more comprehensive and holistic engagement.

Although it has not been proven scientifically, I am drawn to the concept of telepathy, which echoes the sophisticated communication systems observed in the animal kingdom. For instance, elephants communicate through infrasonic sounds that are felt rather than heard, transcending human auditory capabilities and suggesting a form of deep, vibrational communication. Similarly, whales utilize complex songs that may be heard across long distances underwater, indicating a level of sonic interaction that blends sensory and intuitive understanding. These examples illustrate how telepathy can be seen as a manifestation of an innate human connection that transcends spoken language, involving a discourse through sensors, embodied knowledge, and vibrations that convey emotional states and intentions. In this context, I perceive telepathy not as a mystical phenomenon but as the transmission of thoughts or ideas through paths other than the known senses, encompassing a wide spectrum of frequencies in magnetic fields. My interest is particularly piqued by the unspoken cues and instinctive exchanges that occur beyond words, much like these animal behaviours that suggest complex, non-verbal forms of communication.

The concept of innate communication may remind us of the bonds we share with other species and the capacities of our sensory experiences. Although spoken language—the structured, verbal, and textual forms we learn in school—holds a significant place in our lives, we balance it with subtle cues, tonalities, and sensations, which together shape a non-verbal framework. This holistic mode of interaction transcends cultural and linguistic boundaries, conveying feeling, intent, and meaning. By facilitating interpersonal connection and the sense of a shared humanity, it can bridge divides and dispel misunderstandings, promoting unity among diverse individuals and communities. Exploring these natural systems may help us better understand ourselves and our interconnection with all living beings in the world around us.

Classroom of Language has been a significant artistic journey that has ventured beyond the basic transmission of information to offer visitors and participants a sense of belonging and empowerment. Through hands-on exploration and thoughtful responses, visitors interacted with language in unconventional ways, forging bonds and cultivating empathy. As I reflect on this body of work, I am grateful for the opportunity to share my narrative and explore a spectrum of communication tools with others. Together, by embracing a multitude of expressive forms and questioning conventional standards, we can continue to nurture a more inclusive society in which everyone feels valued, heard, and welcomed.