May 9, 2022

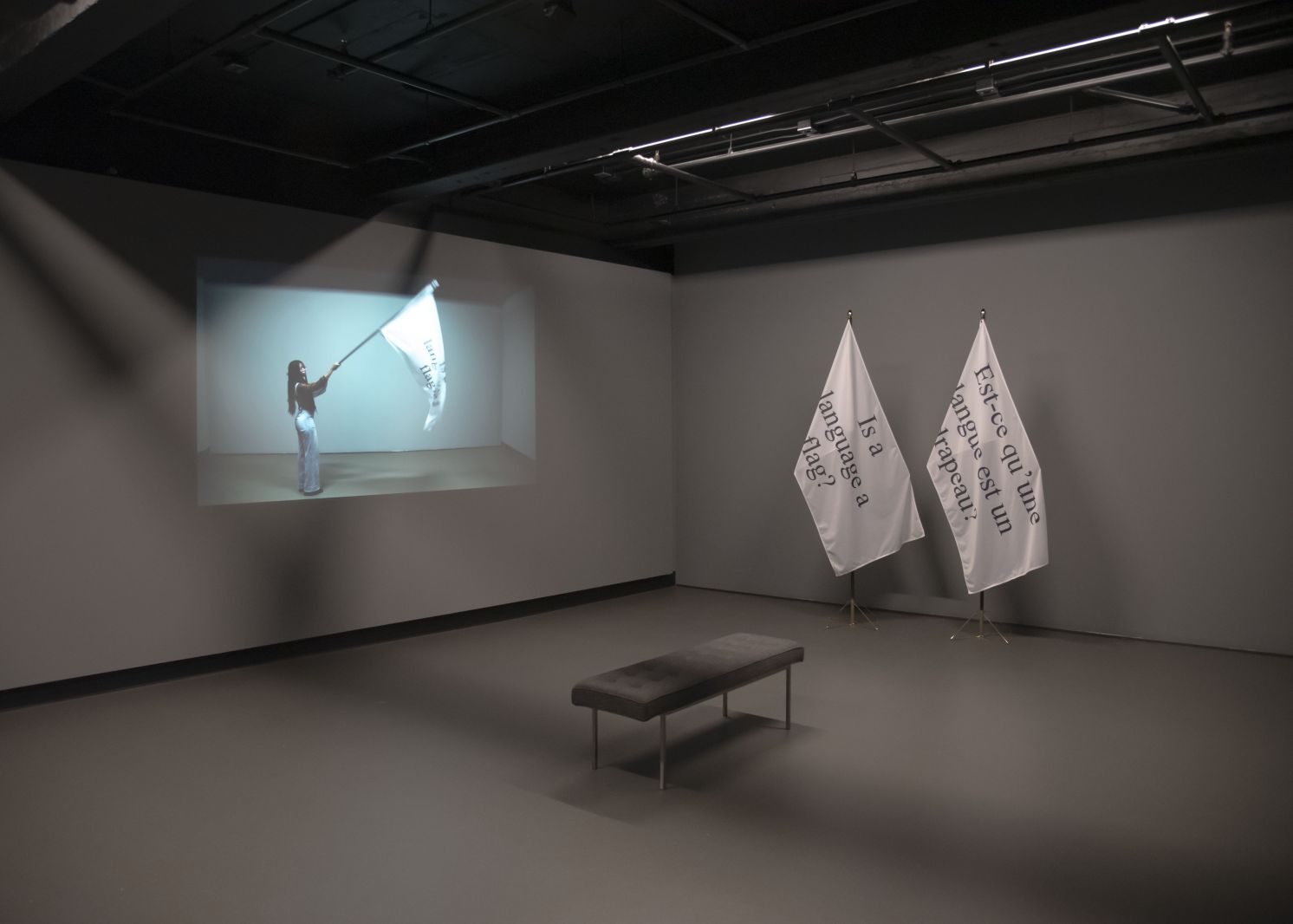

As my contribution to articles comes to an end, the second project I would like to touch on is entitled Is a language a flag? Created in 2021, the work is an installation consisting of video work and custom flags that speaks to the often underexplored relationship between land, nationalism and language as that cultural carrier that bears the mark of encounters between different nations.

The piece investigates how languages such as English and French are precariously balanced as both that unifying factor that brings together disparate peoples and regions – creating a sense of belonging – and a site of ongoing violence through which the legacies of colonialism and imperialism are shown to be omnipresent.

If language is belonging then the piece asks: to whom do we belong and to whom does a language truly belong?

In The Language of African Literature, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o examines the belief among certain African writers that colonial languages such as English act as a uniting forces ostensibly capable of “unit[ing] African peoples against [the] divisive tendencies inherent in the multiplicity of African languages within the same geographic state” (Ngugi, 1986, p. 7).

Through wa Thiong’o’s reflections, the paradox of English or French becoming the common language with which to fight against white oppressors becomes too obvious to dismiss; one must contend with and face the space these languages have taken even in movements against (neo)colonialism. In wa Thiong’o’s analysis, the White Savior Complex, it appears, extends even to colonial languages which, in wa Thiong’o’s words, are often seen as coming to save African languages from themselves.

As wa Thiong’o’s reflections lay bare, language can function as a control mechanism through which to lay claim to entire regions and peoples. When I speak English, who claims me? When I speak French, who claims me? And what does it mean to claim those languages as my own, as my first and second languages? What does it mean that I feel most at ease speaking in these languages – that I dream, think and make sense of the world through these languages? That I must turn to them to make sense of a mother tongue whose words grow more foreign to me with each passing day?

When all is said and done and all that remains for me are these languages, will they be heralded as my savior, as that which allowed me to live? Who will keep count of what was lost? Of the plurality of languages that were deemed divisive and weeded out, one by one, over the course of centuries? Who will remember?

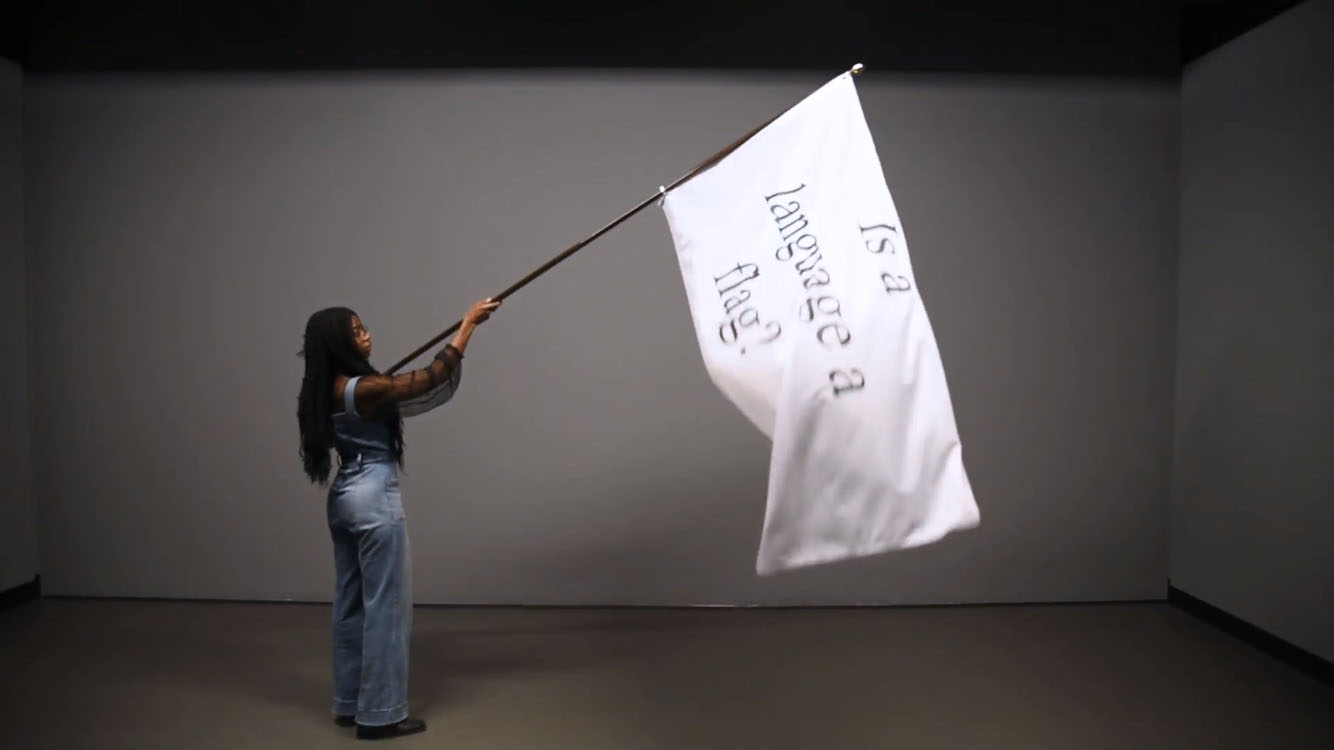

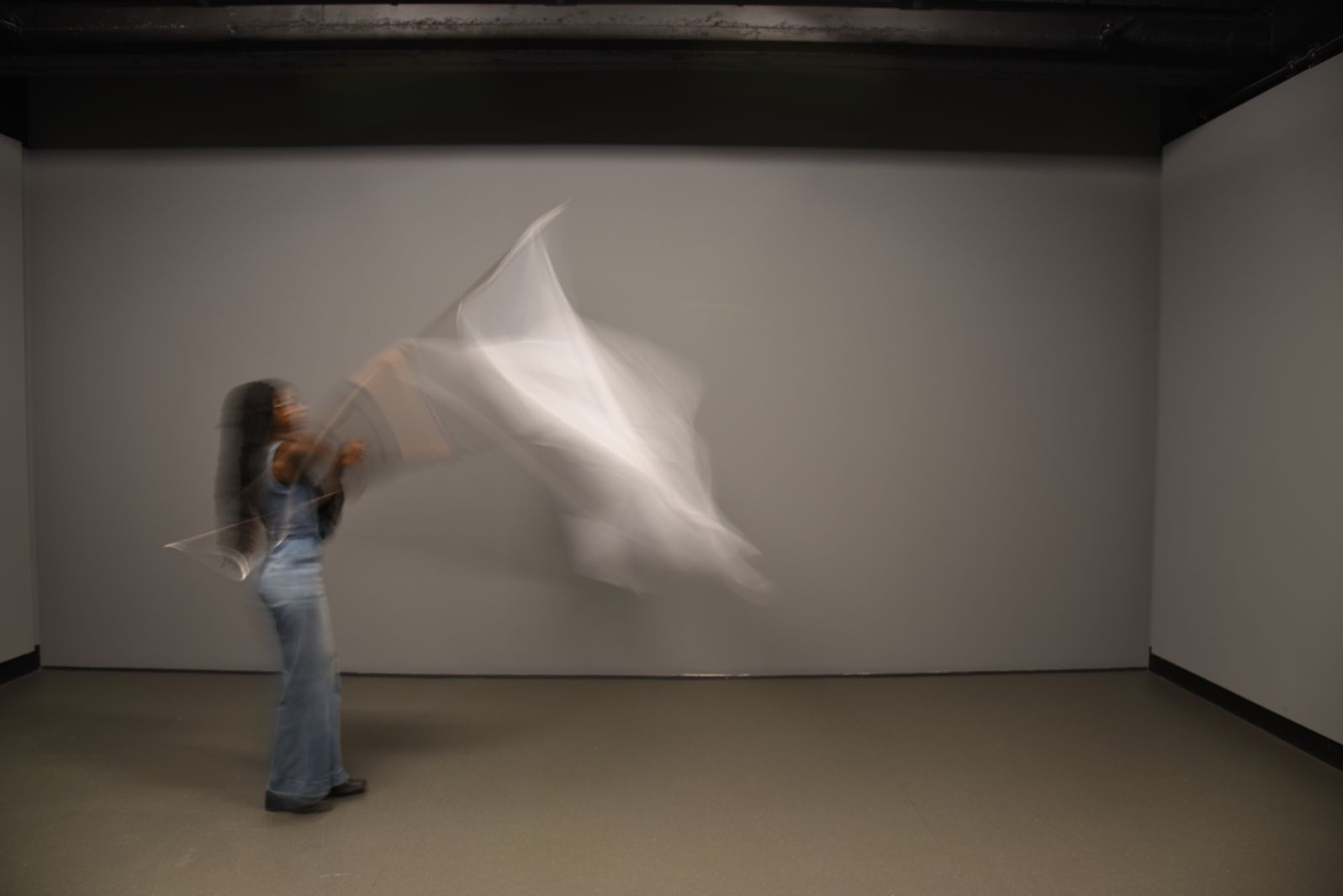

Is a language a flag? sees in language a performance that is rehearsed on a daily basis, in interactions as simple as asking for directions or calling a loved one – each time marking us as belonging to a particular nation or ethnic group as words tumble out of our mouths, dressed in different accents and slowed and sped up to different cadences.

The piece highlights the performative elements of language through the act of waving a flag – an act of patriotism that is associated with nationalism, a word that at once describes pride in one’s own nation – its history and culture – as well as the ills this feeling can engender when nationhood is understood in terms that fuel division and dispossession, and all too often ultimately result in violence.

Having moved from Nigeria at the age of five and growing up in Gatineau, Quebec, I was forced to learn French to navigate a new and often hostile public life, all while English quickly displaced my mother tongue as the language we spoke at home. While my brother had a natural gift for languages, I struggled daily to fully master either language, growing more timid and reserved, even as I turned to writing in English as an escape and a way of expressing myself. Two languages I was forced to learn, neither fully offering a sense of belonging and both eroding my ability to speak the language of my forefathers.

Held tightly in my hands – at once a caress and a sign of a heavy burden – the flag and the work itself asks: to what extent is language itself performance? And performance of what?

___

Nna m, how do I say: The sun never sets on the British empire?

January 24, 2022

Rather than a fait accompli, The ancestors are meeting because we have met was always, in my mind, but one of a stream of ideas slowly coming to the surface, straining against the weight of race and Blackness as concepts that had until then dominated my understanding of self. In my turn towards language and its relationship to imperialism lies a trace of a long-standing desire to delve deeper into my relationship to Nigeria, to this place where, as my father often reminds me, my umbilical cord is still buried, cementing my relationship to the land. And so, language, imperialism, and this Nigerian identity – this Igbo identity – have become inextricably linked. As I attempt to tease them apart, to re-arrange them in new configurations, to stretch the limits of their conceptual weight and boundaries, one saying has become and remains foundational.

I first came across the phrase “the sun never sets on the British empire” in 2020. I was exhibiting alongside Kapwani Kiwanga and Rajni Perera at the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa as part of Made of Honey, Gold and Marigold, a group exhibition curated by Geneviève Wallen. Sitting on the bench, staring at Kiwanga’s The Sun Never Sets – a montage of sunsets filmed in various countries once united under the British empire – I feel and reckon with its metaphor for the breadth, scale and magnitude of British imperialism as I watch the sun set over landscape after landscape. Awash in the golden hues of the montage, the quote lodges itself in my mind.

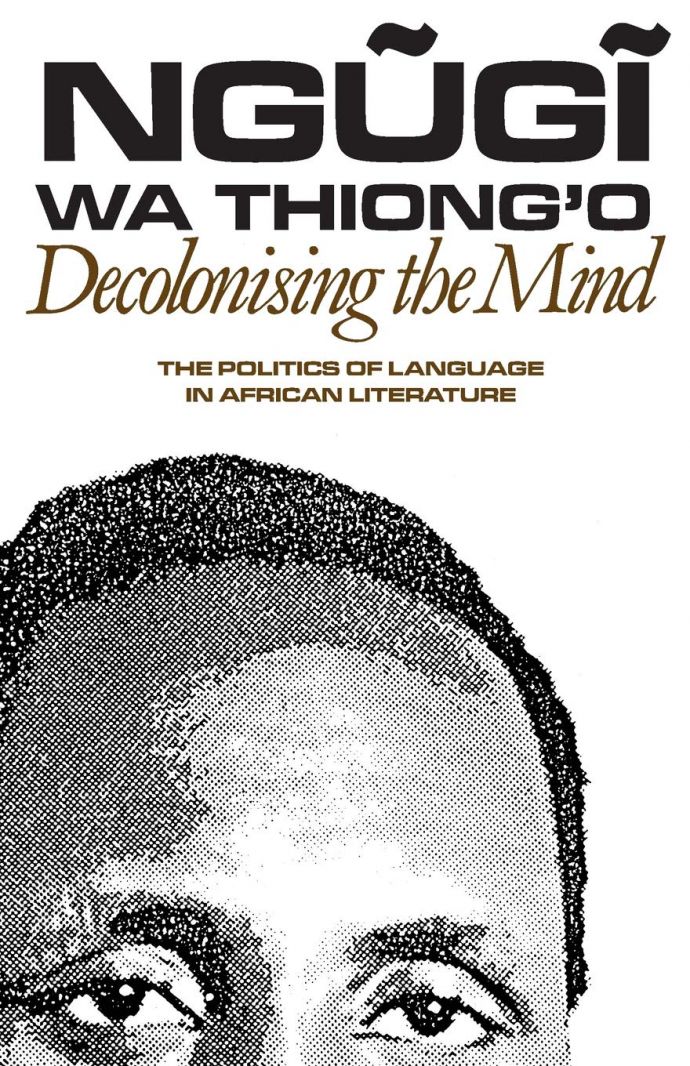

When next I think of the saying, I have already begun to work on The ancestors are meeting because we have met. I carry a copy of Decolonising the Mind by Ngugi wa Thiong’o – a Kenyan author once jailed for writing a play in Gĩkũyũ, his mother tongue – with me everywhere, turning to his writing on the plight of African Indigenous languages to better understand how language becomes a tool of imperialism.

I first encountered the book on the shelf of the flagship Waterstones in central London in November 2020, its white and black sleeve, with wa Thiong’o’s eyes peering up from the bottom, understated but effective. There I was in the heart of empire, a haunting that I experienced each time I saw a parakeet in Hyde Park or a palm tree around the corner of my flat, always questioning how they ended up there – as though my journey was much different. Ultimately, I had placed the book back on the shelf, not yet ready to engage with the question of how my relationship with the English language was an equally living and breathing reminder of the scale and reach of British imperialism.

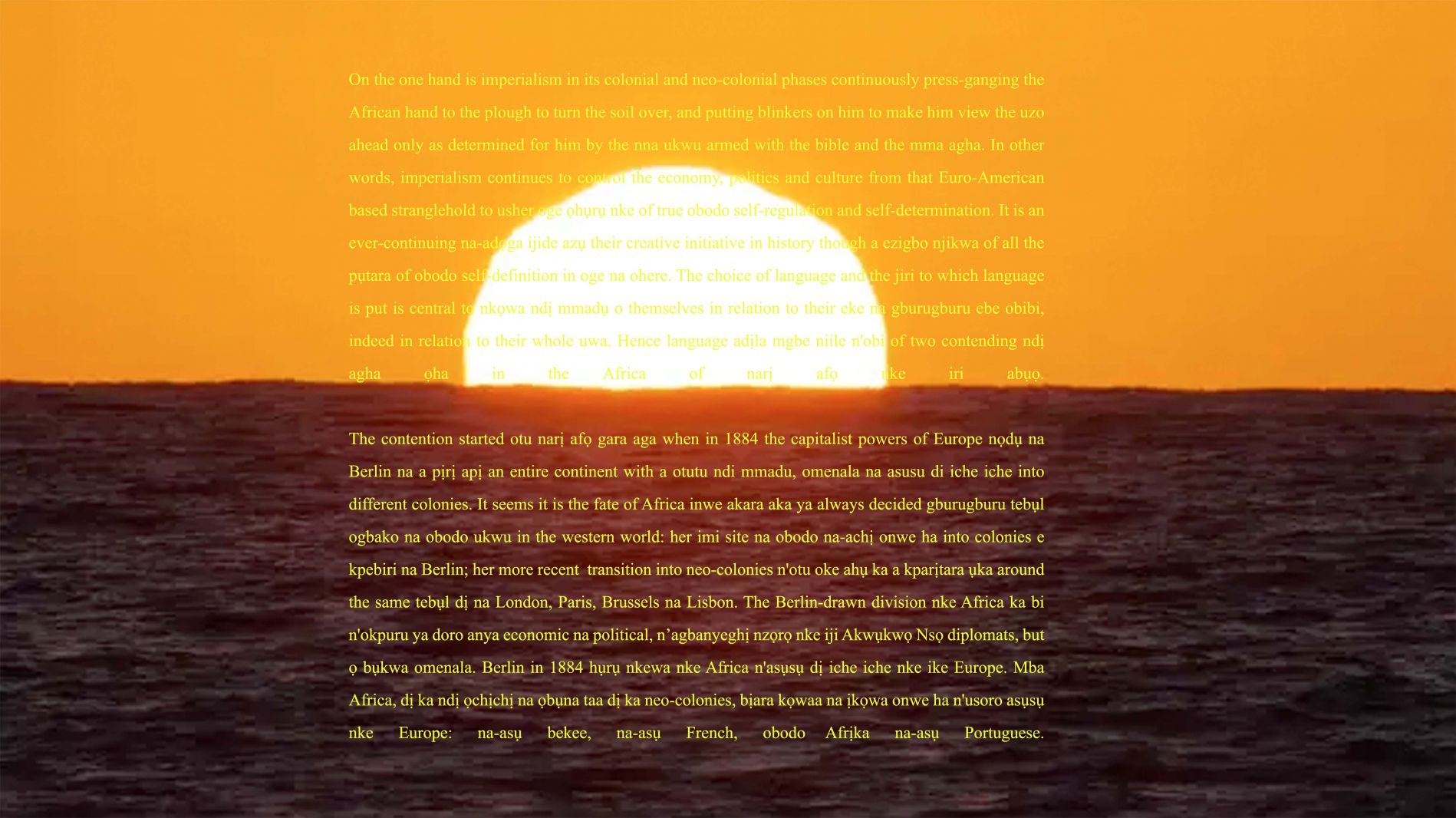

Months later, I overlay wa Thiong’o’s words from the book – his last in English before committing to publishing only in Gĩkũyũ, – over an image of a setting sun, a composition with a significance I only begin to understand in hindsight.

As an Igbo woman, the image and metaphor of a setting sun is a doubly loaded one. The image of a half-sun figures prominently on the flag of Biafra, an Igbo secessionist state whose birth in 1967 and demise in 1970 marked the beginning and end of a civil war in Nigeria. The rest of the flag features colors largely associated with Pan-Africanism but whose meaning for Igbo people harkens back to experiences of war: red for blood shed during the war, black for mourning, and green and yellow for prosperity and a bright future. Yet it is the image of the half-sun with its eleven rays that has become a key part of Igbo iconography and an allusion to what Biafra – “the land of the rising sun” – represented.

Biafra existed for 30 months; it was forced to surrender after more than two million Biafrans – many of them children – died of starvation owing to a total blockade of the region by the Nigerian government, aided by the British. At the heart of the conflict were the arbitrary borders drawn in boardrooms in Berlin in 1884 through which Britain had laid claim to large swathes of West Africa; a system of indirect rule that fostered division across the country, putting in place foreign systems of governance that created new hierarchies and antagonisms; and a ‘civilizing mission’ that deployed both religion and education – language being a common theme as missionaries spread both the English language and fear of God – as tools to gloss over exploitation and expropriation.

I often think of what to make of this visual of Biafra as the land of the rising sun and the countervailing image of Britain as the empire on which the sun never sets. I think of the weight of this half sun that is at once perpetually setting and rising – both a haunting of the past and a specter of the future. I think of imperialism as a shadow that is always both behind and ahead of us, that clings and grasps and shudders, a dying gasp forever on its lips.

Over the image of a half-sun – a rising sun – wa Thiong’o’s musings on neo-colonialism and language slowly fade from English to Igbo.

___

Nna m, how do I say:“Language is both the wound and the bridge”?

December 15th, 2021

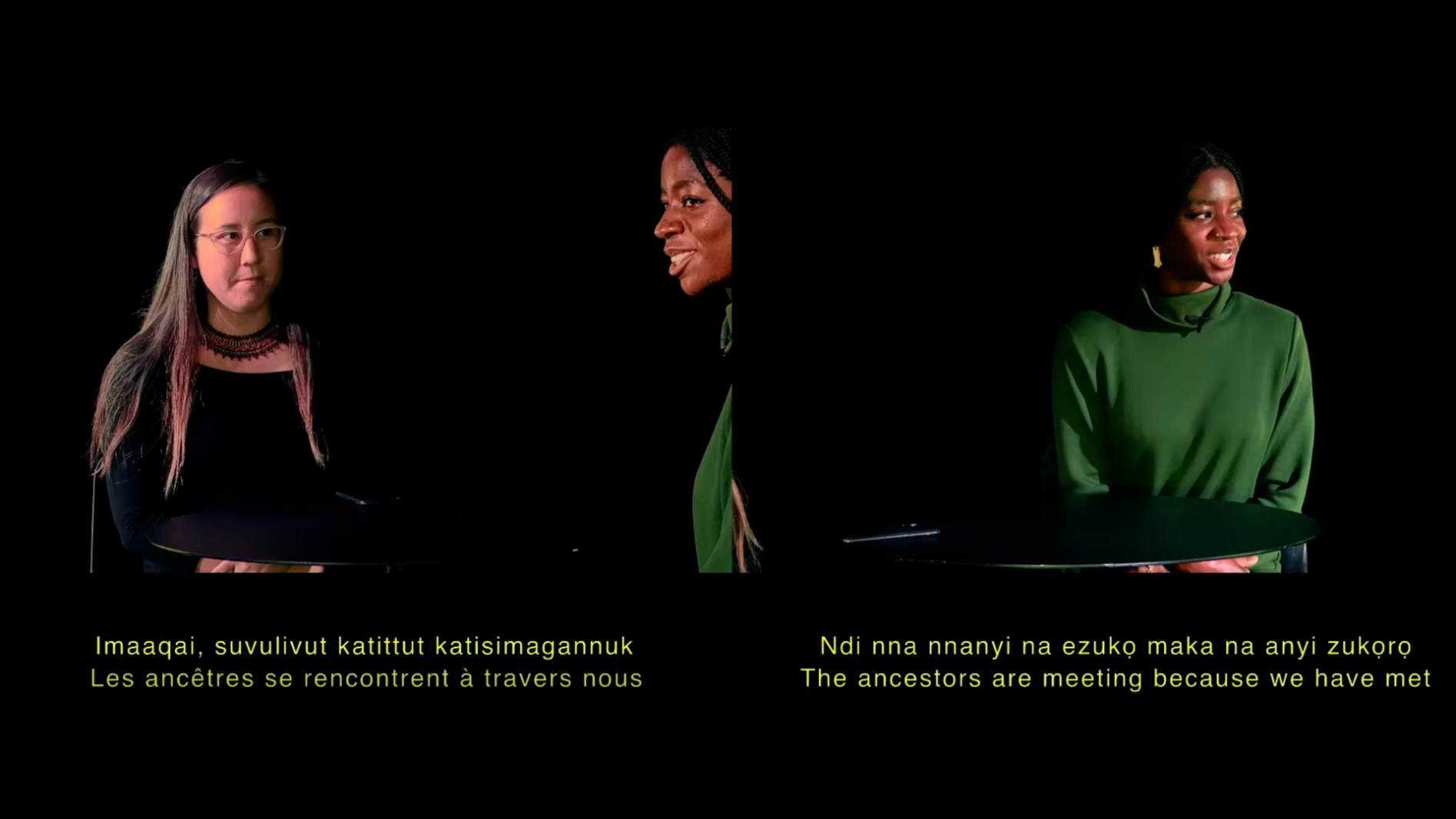

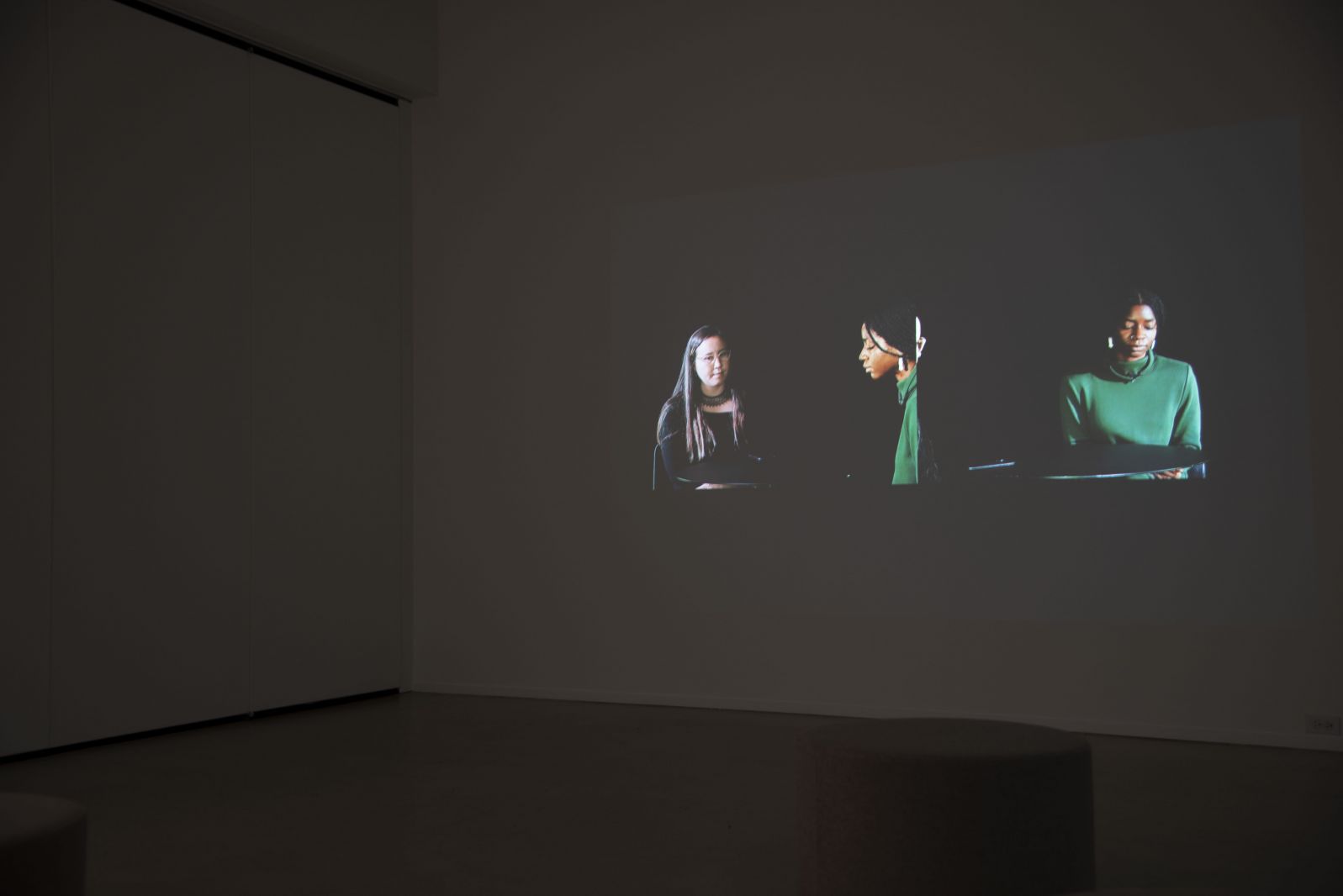

Watch an excerpt of “Ndi nna nnanyi na ezuko maka na anyi zukoro / Imaaqai, suvulivut katittut katisimagannuk / The ancestors are meeting because we have met”, by Kosisochukwu Nnebe (in collaboration with Katherine Takpannie)

Part I

“[W]hen you talk to knowledge keepers and elders, like the first thing that they tell you, if you want to get reconnected, is to learn the language.”

These are the words of one of the participants of a focus group I organized, back in May of this year, as part of my dissertation researching Black-Indigenous relations on Turtle Island. I’ve been reflecting on the complexities of my presence as a Black woman on these lands since 2017, when, as a representative of the Canadian federal government, I traveled across the country engaging with Indigenous communities to develop a new national food policy. Although my family first migrated to Canada from Nigeria when I was five years old, it was only as I moved from community to community, journeying from Yellowknife to Thunder Bay to Nunatsiavut, that I was forced to confront my own role and complicity, as an employee of the State, with the settler-colonial project that had displaced these communities from their ancestral and traditional lands.

As I learned more about Indigenous food systems and worldviews, I began to experience a feeling of loss that had until then only ever existed in my unconscious as an intangible but omnipresent sense of malaise. I began to question my own relationship to the land of my ancestors and the knowledge and ways of being it held. I soon realized that my family’s migration in 1998 had entailed a distancing more extensive and broad-ranging than I had initially understood– a separation that was at once physical but also cultural and epistemological, and that had, unbeknownst to me, begun before I nor even my mother had been born.

My experiences between 2017 and 2019 dredged up many issues related to the possibilities of relationality between Black and Indigenous peoples on this land that were addressed in They Forgot That We Were Seeds, an exhibition I curated at the Carleton University Art Gallery in 2020 that brought together eight Black and Indigenous women artists. But so many other questions remained after this project, some being more personal than could be explored through that particular format, and that I have only begun to explore now in my capacity as an artist.

Part II

Language had not been part of the topic guide for the focus group, and yet we butted against it at all times. There we were, Black and Indigenous, women and two-spirit people, talking about how language can connect us to our ancestral knowledge, yet communicating and sharing in English – the language that has enacted so much violence on our native languages, and yet is what allowed us to share that particular moment.

Later, I read the line by poet Adrienne Rich: “It is the oppressor’s language, yet I need it to talk to you.” The words stay with me for days, weeks, settling heavily on my tongue as I speak them out loud. English is my first language – the only language I feel comfortable communicating in, even when I stumble on words or find some elements of it nonsensical – so it had never occurred to me to truly question how its omnipresence in my daily life speaks to a legacy of colonial violence and intervention that binds me to other colonized peoples. But there it was, in this meeting of Black and Indigenous women and two-spirit people, revealing itself to me as both the wound and the bridge.

Part III

“Ndi nna nnanyi na ezuko maka na anyi zukoro / Imaaqai, suvulivut katittut katisimagannuk / The ancestors are meeting because we have met” emerged out of a desire to grapple with language as both a site of colonial violence and a potential space for healing and restitution. In many ways, the piece is an outgrowth from They Forgot That We Were Seeds, building as it does on the relationship I developed with Katherine Takpannie, an Ottawa-based Inuk artist and one of the artists in the exhibition. From a curator-artist relationship, we quickly developed a deep friendship that I constantly refer back to when I think of otherwise forms of relationality between Black and Indigenous peoples on this land.

In the video performance (my first), Katherine and I attempt to speak to one another in our respective native languages: Igbo and Inuktitut. As we struggle to speak our mother tongues, turning to parental figures to help us in translation and diction, the work collapses time to speak at once to legacies of past and present colonial violence, but also to a different envisioning of Black and Indigenous futurities. All the while, it centers our relationship – that between an Igbo and Inuk woman – in a way that challenges and pushes forward current discussions around Black-Indigenous relations.

In my eyes, however, this is only the beginning.