During the summer months of 2018, Artexte welcomed British artist Richard Layzell for a short research residency in the collection as part of a broader artistic project as he traveled across Canada. Following a small gathering with local scholars and artists, Sarah Watson, General and artistic director of Artexte, and Richard Layzell sat down in the gallery for a chat about the artists’ practice and his experience in the collection.

SW I’m curious about what sparked your interest in this particular collection. I know you are travelling for a year, but what was it that made that this kind of research seem of interest to you to stop at this site, here?

RL Well I guess I was introduced to it from London. The conversations I was having with Ben [Cross] at the LUX were really interesting. Not everybody gets what I’m doing, and he really got it and then he said: “Oh, you must come to Artexte.” So that lead to the contact [between you and I]. Then what I realized while I was here [in the collection] is that we have so many artists in the UK and we have nothing like this. Nothing remotely, really. So, as a resource it’s sort of extraordinary. And then I looked online on e-artexte and I thought “What if there is anything about me?” And there were 16 entries [1]1 (1979-2008). Dossier 440 et. al., Layzell, Richard., and I was like “Whoa!” So that led me to this thought: first, I would go through my own archive, pull out anything I had to do with Canada, my work here, reviews, publicities and things.[2]2 (2018). Richard Layzell at Artexte. I brought all those with me [to Montreal], thinking that I was in some kind of- imagining I was in some kind of a Canadian area [in the collection], but of course I’m not. I’m in the European artists area. I also mailed some stuff ahead because I thought it would help contextualize the work I did in Canada. One of the pieces I did here in 1983 I took back to Canada House in London and it sort of became another piece there. That little body of work was quite important to me.

The thought about Australia, I haven’t mentioned this before, but when I was a student in London, I finished my BA and then my parents immigrated to Australia. My brother was already there. So, my whole family went, and they said: “You’ll come, won’t you?” And I said, “You know I can’t”, really knowing I probably wouldn’t go. I was doing my thing in London. I was going back to do my master’s at the Slade [School of Fine Arts]. In the intervening year that’s when I went to the States and that’s when I had a lot of the First Nation’s experience there.[3]3 (2018). Richard Layzell at Artexte. So then, I didn’t go to Australia, they stayed there for about a decade and came back. My brother is still there! I went to Australia last year and I was thinking about what would have happened if I had gone. What would have happened to me as an artist if I’d gone to live in Australia? So, I’m thinking of taking that thought back with me in October.

And then when I sort of felt my presence here at Artexte within the archive, I thought I would do the same thing here. Because as I mentioned [during lunch on] Wednesday, in the mid-80s I had seriously thought about moving here [to Canada]. So, to occupy this sort of psychic space – “If I had been living here, what work might I have made?”- is a kind of intriguing thing to explore while I’m here. It sort of fits with the nature of the archive.

And I guess the final bit of this is that – also as I mentioned on Wednesday – I live with an archive, my own archive. And it’s kind of too much some time. I move it and put in my library/studio and put a bit of it down, but I worry about it you know. Do I put it all there? And because of recently having a lot of building work done on the apartment, I’ve pulled stuff out and started opening them and I had some good surprises. I’d forgotten what was in those boxes, but I guess in a general way this archive feels a bit of a weight and it feels like old work. Okay, I’ve stored what I have and, you know, I don’t produce objects. Actually, the objects disappear, so this is what there is. But it’s old and I had a weight of a career of 40 years or something. And it’s like “Oh, I can’t look at it.” And I kind of go into rejection mode of it because I’m always involved in what I’m working on at the moment. But I think being here, it’s like… Discovering that card from Mercer Union in 1983 [in my artist file], it was like I had a real sort of resonance. It’s different. Because I could have found that card at home and it wouldn’t have affected me. But finding it here, within an archive of materials put in a folder saying, “Cards from 1980 to 1990”, it’s like I felt a real sort of significance of how a personal archive within a bigger archive is really meaningful. It helped me feel more, I guess. Without overstating it, I can feel more integrated as an artist by relating in this way within this archive.

SW Well that’s great! You said some of those things on Wednesday, but as someone who works in the collection every day, we don’t always – and you know we often welcome people who are doing secondary research, like curators who are doing research on a certain artist – but it is quite rare for us, strangely, to welcome artists who are inventing or imagining histories of themselves and finding themselves in this site. It’s oddly quite rare for artists to come and research where they are found physically and historically within the collection. And it’s an experience that we know must happen, but I haven’t heard it explained to me in that way, the effect – the relation of the private with the public, accessible only to one and accessible to many publicly. So, thank you.

RL Well I wouldn’t have predicted that, it was one of those sorts of “epiphany” kind of moment. If I’d thought about it ahead it would have been kind of different. I hadn’t planned for it.

SW And also imagining yourself, how you spoke to us on Wednesday, finding out physically where you would have been in the “L” folders. [laughs] You know? There are these kinds of very moving moments, but there’s also these moments of “How do I fit in here archivally?” “How would I have been classified physically?”

You kind of answered my second question, but how do you feel that art documentation somehow enriches your thinking and your practice? We’re talking about this instance here, but did you want to speak of anything else about collections or archiving within your practice (which is of course voluminous)?

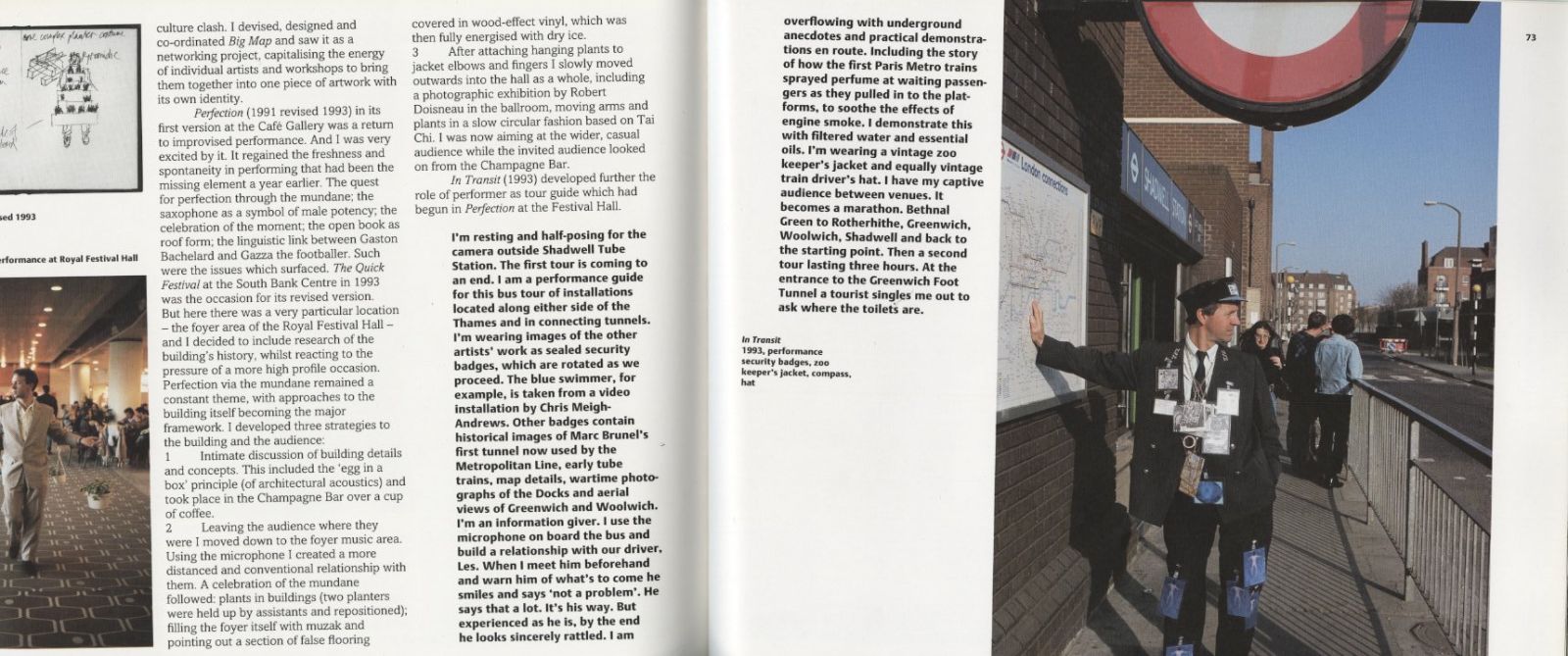

RL The concept of self-archiving I have explored before in a different way. I revisited some old videotapes from 1980 and I made a new work when I related to these pieces and that, I think, was interesting. It was a kind of strong piece of work people said. But this is in relation to my one-year project which may not, I realized while I’ve been in Montreal, be a one-year project. It may just carry on. The self-archiving element is more subtle, I would say. I feel like it’s not really navel-gazing. It’s just sort of acknowledging one’s own history. That can be a very positive thing. I think being out of my country – I’m not in the UK, I’m in Canada – it’s easier to have separation of a kind.

SW Yeah, you said “navel-gazing” and it’s also interesting, because to say the words “I’m researching myself” without knowing the process, of course it could be perceived that way if you just heard that sentence. But what you’re doing is I think so applicable to the many questions that educators, artists, makers ask themselves at very different points in their lives. When you were speaking Wednesday, part of the questions were: “How do I start?” “How do I not give everything to others or away?” Beyond the individual questions, there is that question of “How does one reserve energies of different kinds of making?” And perhaps looking at a collection, looking at what’s been produced, not as an individual but questioning the private production and the public output, is a question that can be addressed to all kinds of people who are making things, right? Putting out something, whether it’s education, teaching, art-making or exhibition-making; how does this somehow fit into another [practice]? We talked about ecologies as well on Wednesday – and this is really an ecological project about how is your practice moved transnationally from the outside, from the meta-level. How is it traced within this? But not only yours but so many others. How could other people do this similar kind of research? I think that’s one of the other things. That this is there if one would like to trace.

RL I think another aspect that is coming through my thinking is my plan for this bigger project called The Naming, which I didn’t really talk about much on Wednesday. The very enticing new concept that came through in the early months of thinking about it was that there would be some writing, which would become a work of fiction and that I would aim to have it published, because I have quite a strong relationship to text. But then, I was working with a fiction writer in the summer, a novelist who teaches fiction writing, and I began to think for The Naming, for this persona, Kino Paxton, who has evolved in it. But actually, I remember when I worked on the book that I left with the archive called Enhanced Performance (1998) with Deborah Levy, who is now a very famous novelist in the U.K.[4]4Harding, Anna and Layzell, Richard (1998). Enhanced Performance. Colchester, England: Firstsite. She’s big and she said to me: “Richard, you don’t always have to tell the truth.” I felt awkward when she said that because I believe in truth. However, when I thought about her comment in relation to this new project, I was thinking I can fictionalize if I want to. So I have started some of the writing about things that happened last summer in Greece and I have fictionalize part of it. That enabled me to think about how we as artists – and this is in relation to the archive – we create our stories about what we made. So that card I pulled out [Mercer Union in 1983] has an image of a piece I’d forgotten about, that I did in the south of England and that I used on that card for a particular reason. I know why I used it and what sort of impression I wanted to give and then I know the piece I made. It was kind of connected to my then absorption in the peace movement. I think I’d been living in a house that became [inaudible] London office. I was kind of immersed in the peace movement and in feminism. My narrative about that piece [the image used on the Mercer Union card] is all that time. But do we revisit those narratives? Do we go back and think: “Actually, can I look at this work differently now that I’m 10 years or 20 years older or something?” “What was the story I made up about it?” Because we always do create a narrative that may not… That can be open to question. So, I think that’s another thing that the archive might allow to happen, to encourage people to revisit work from a different perspective.

RL The concept of self-archiving I have explored before in a different way. I revisited some old videotapes from 1980 and I made a new work when I related to these pieces and that, I think, was interesting. It was a kind of strong piece of work people said. But this is in relation to my one-year project which may not, I realized while I’ve been in Montreal, be a one-year project. It may just carry on. The self-archiving element is more subtle, I would say. I feel like it’s not really navel-gazing. It’s just sort of acknowledging one’s own history. That can be a very positive thing. I think being out of my country – I’m not in the UK, I’m in Canada – it’s easier to have separation of a kind.

SW And from a distance, from these chronological distances of 20 years as a person now looking at the story that the person then told. Or remembering it.

You’ve talked about some of the unexpected things, but one of the questions that I wanted to ask is what’s something very unexpected that you’ve found? You’ve already told us, and me, about a couple of unexpected experiences, so I don’t know if you wanted to add to that.

RL Well, before I came to Canada I hadn’t really – I think my memory was around the artist-run centers and how much I kind of enjoyed that relationship. I wanted to reengage with those artist-run centers and celebrate them because we don’t have quite the same equivalent [in the U.K.]. So, the unexpected was obviously that it changed. The systems are little bit more formalized than it was then. But also, I guess I hadn’t expected to find that kind of profound connection to First Nations’ issues. So when I arrived on Monday, that was the first question I asked because by the time I got here I’d been sort of – I’d just come from Fredericton where I’d been to the local First Nation community [Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqey] to have an experience that would be personal. Then I had the sense that “I’m going to go to Australia…” and I eventually did get to Australia when I finished my master’s. I was a school teacher there for a couple of years. I was going to go to Australia and teach, but I wasn’t allowed to because I didn’t have the right avocation. That’s when I stopped teaching in highschool and I became a self-employed artist. So that trip to Australia was kind of important, it forced change. I might have become a highschool teacher. Quite possibly, I think. And then when I was in Australia, nearly the first thing I did was I went to Redford to the – it was an office of Aboriginal affairs, I walked in and I said: “I’d really like to help.” Really, I cringe when I think of it. It was with good intentions and the response was just kind of: “Oh yeah?” It wasn’t an unpleasant response, it was just sort of slightly bemused I guess. And so, when I thought about doing the same thing here, now, with more understanding and knowledge and experience, I was thinking of the position that I would take – again I talked about this on Wednesday – which is that I’m not Canadian, I’m English. And that’s different. My ancestors came here, and this is the result. It’s more – I’m getting quite emotional talking about it but – it had more kind of integrity, coming from that place. When you’re saying “I’m a visitor” because I am a visitor, but it’s also my heritage. Those were my ancestors who did these just unspea- unspeakable things!

So, I think the fact that when I arrived in Halifax and Bruce Barber [professor at Nova Scotia College of Art & Design] had the radio on every morning and there was stuff about reconciliation, this was new to me. I didn’t know this was such a big issue in Canada. I was also very pleased, but it was this surprise, a big surprise, that it would still be a thing. I don’t know how I’ll handle it completely, but it has been big and will continue, I think, to be big. And also, the link in terms of ecology in my project is that that was where it began before I got to Halifax. I was thinking “What would I like to see?” It was about First Nations and thinking about a relationship to the environment that is holistic. That’s what I’m sort of driving at in my research. So that was one unexpected thing.

The other unexpected thing is much more like I’m being kind of slightly mischievous in going through the archive. Going in and out, just seeing what happens. Certain people have come back to me, into my life, that I’d forgotten over the years. One of those I met with last night, but there are others. There is also who I find in the archive that I didn’t know about. Would there be some chance to meet some people, the artists? I don’t know.

SW Yeah, I mean it is. It was complicated the first couple of years, but we feel very secure here because we know that we can’t be kicked out in the middle of the city. Which is always – as you know, you live in London – is always like art organizations come to areas and they make them vibrant and then they get priced out. For us to be able to have the Ministry of Culture help us with the mortgage here is a big thing. It’s a big thing that makes our collection protected, so that we can look after it. It comes with its share of questions about ownership and the questions that come around it, but it’s important that this is central and public, you know?

And then I just wanted to know – and this is something that you can think about or not but – is there something that you think should be here? Anything that’s not within the collection maybe or something that you think could be here that’s not here.

RL Oh wow, I hadn’t thought about that! Um, well… I guess it could be kind of more social, could there be a place where we can have coffee? But then there’s the risk of the archives getting damaged, I suppose…

SW No, you’re right. It’s interesting what you’re saying because we are always thinking about how to balance the certain type of austerity needed to look after these things and how to make it more welcoming and nice for people to be around and have conversations. Tell me what you think!

RL Just that, I’m just thinking coffee. And it’s kind of there, but then you know in the UK everywhere’s got a café. It’s like a disease! Everyone makes the best coffee and it’s too much! It’s gone the other way, so they’ve taken over the venues. But there may be something around a kind of way of being here that’s something different. I’m sure you have school groups and stuff like that.

SW You’re coming at a particular time [summer break 2018] where there’s usually a lot more people coming in and out, spending time, being in the gallery and there are chairs around the gallery where people stay and talk. But I do find that it’s a challenge because – not a challenge but, how do we make it nice for people to hang out without monetizing coffee and making it a business that we would then be obliged to run. And one of the things that we’ve done during the school year is offer free coffee and put out chairs, or just have a tea corner – you know, a little tea trolley [laughs] – or just have a place where people can be doing deep research, but then kind of escape and sit in another social place. So, it’s important that you bring that up because it’s something that happens depending on what we are doing at a certain time, depending on the exhibition. Sometimes it’s in here, depending who’s coming through. But I do really agree with you. When we first started here, down the hallway there was a bookshop, it was an art bookshop. What happened is that people would come to buy books and they would start chatting and we had chairs in the hallway and people just grabbed coffee or something to drink and hung out in the hallway and it sort of became sort of an ad hoc café. Without that, that’s now for us to think about how to make it a place to stay in other than when you’ve got your head in the books. We have to figure that one out.

RL Well I’ve thought a lot about it, which I brought up with Hélène [Brousseau, Artexte Librarian]. A second kind of observation is that there are two sets of stacks in the collection facing each other, one is organizations in Quebec and the other is organizations in the rest of Canada and they’re the same size. I said to Hélène: “Well, how come?” She said: “Well it started here in Quebec and we are trying to get more people to send us stuff.” And so I said: “I’ll tell people they are not represented.”

SW Advocacy! [laughs]

RL Yeah! You can’t go around and meet people everywhere. It’s a huge job.

SW And, as you said, a lot of things operate on the social. So, when we work with people from say Calgary, all of a sudden Calgarians start knowing what we’re doing. And we do contact people. But one of the things we discover when we call the Yukon, or we call people in British Columbia, we say: “We’re national, we accept all of these provinces and your work.” And they say: “Oh, but you’re in Montreal so we thought it was only for French publications.” So, there’s often an auto-censorship based on language politics that happens just in the reflex of being in the ROC (Rest of Canada) as we discussed [laughs] and in Québec. So that’s a divide to work on. We’ve been kind of choosing little things. Like if we know we have friends and colleagues in one area, then we kind of go in and start calling people in that area, or if we’ve recently worked with an artist from Newfoundland, then we try calling people in Newfoundland. When you start talking about the physical representation, how could we do differently, how could we do more? But it also traces the history of artist-run centers in Québec, because Québec has so many comparatively to other provinces. So, it is a testament to that, but it’s also a testament to how this country is humongous. [laughs] So how can we be representative of this massive country? There is this sort of “Québec remove” that happens – you heard on Wednesday, the ROC and Québec – that’s something too because the ROC is so completely diverse and non-related to one another. But it’s true, how many hours in the day can we call people and hear their voices and talk with them and let them know that we want to care for things, you know? I’m glad you noticed that, thank you for this!