I am keenly interested in narratives of place. How do available narratives enable us to understand (or misunderstand) a given place? By which processes do places generate their own stories and, conversely, by which strategies do stories produce the places they narrativize? What counter-narratives exist to relativize existing dominant narratives and allow other models to emerge?

Regent Park is a place of fascinating and complex stories. Like the rest of the city of Toronto, it is located on Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg territory. In the 19th century, this area was populated by Irish working-class immigrants who, in reference to their use of domestic yards for the purpose of growing food, gave the neighbourhood of Cabbagetown its name.

Under the sway of dominant city-planning ideas of “slum clearance” and “urban renewal”, the entire southern section of Cabbagetown was demolished during the 1940s. Construction of Regent Park on this vast, bulldozed lot began in 1948, and resulted in Canada’s first and largest public-housing project. Celebratory in its tone, Grant McLean’s film “Farewell Oak Street” (1953) today enables us both to visualize the drastic physical transformation of this neighbourhood, and to begin to conceptualize the entrenched ideologies that legitimized this transformation.

By the late 1960s, such ideologies were openly questioned and then fully challenged in the following decade. The rise to power of a Reform Council during the 1972 municipal election immediately halted plans for sweeping urban-renewal schemes in Toronto. During this decade and continuing through the 1980s and 90s, the northern section of Cabbagetown (and its then newly restored Victorian row houses) was gentrified by urban professionals — while the southern section of Regent Park (and its modernist blocks of public-housing apartment buildings) was subjected to a renewed bout of “slum” and “gang” discourse revealing thinly veiled racism towards its recently immigrated, working-class residents. Stories about Regent Park are largely divided either in celebration of or else in struggle against this discursive process of “territorial stigmatization”, a term developed by Sean Purdy to describe how the displacement of entire communities gets legitimized.

In the mid-1970s, Lillian Allen was working as a community legal worker in Regent Park. She was also working as an education coordinator for ImmiCan, a Caribbean community youth project whose musical offshoots include Truth and Rights and the Gayap Rhythm Drummers. As a member (with Clifton Joseph and Devon Haughton) of De Dub Poets, Allen’s work as an artist was deeply connected within Toronto’s broader dub poetry and reggae music scenes.

Discussing her artistic work in the Riddim and Resistance event with Clive Robertson as part of the Desire Lines series, Allen stated that “the work would not have existed if we didn’t have this political mission and this activist impulse. That’s the context for the work.”

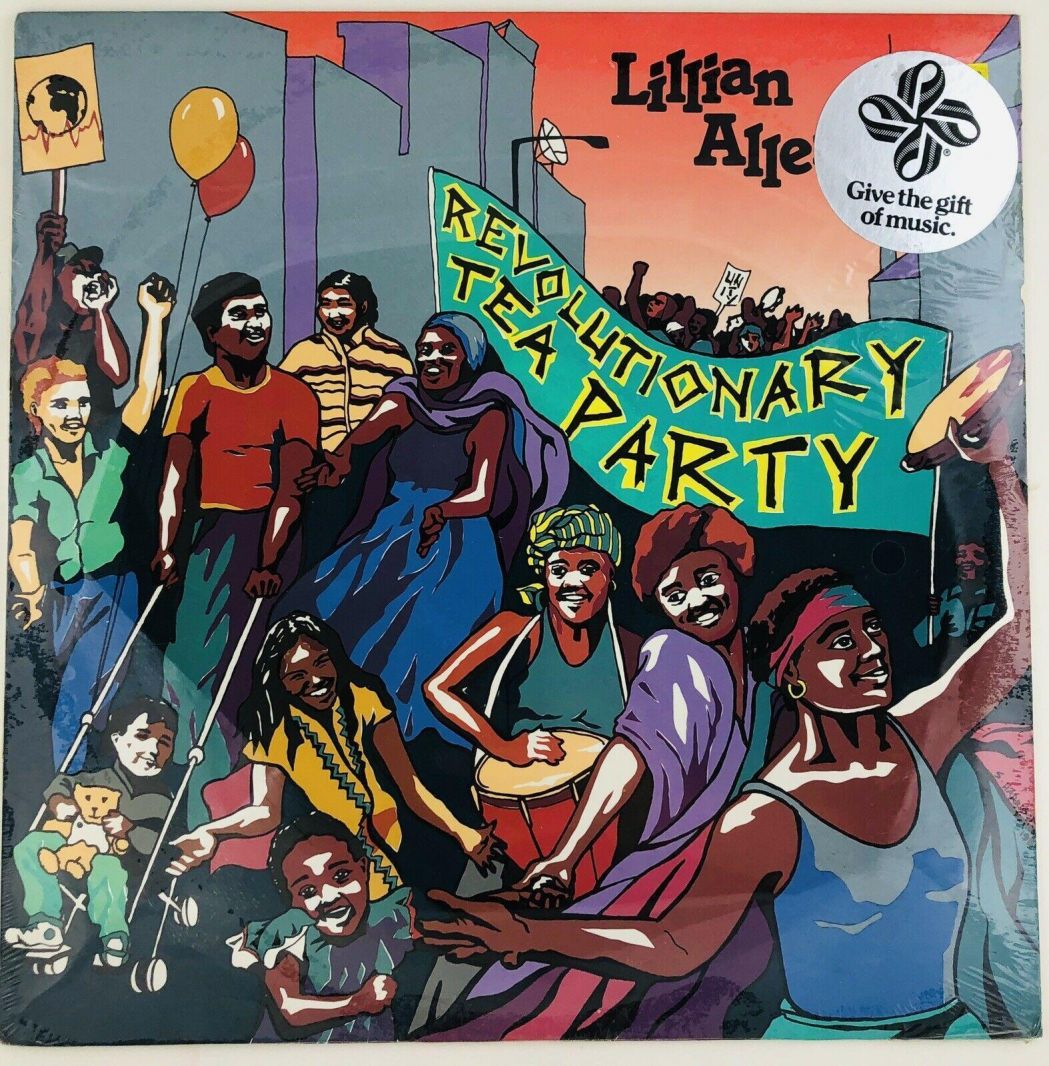

Allen’s track, ‘Dub a Dub Style Inna Regent Park’, was included in her Juno Award-winning album ‘Revolutionary Tea Party” (1986). She uses Jamaican patois to describe a scene of systemic violence confronted by cultural work generated in the Regent Park neighbourhood. Music’s “riddim line” and dub poetry’s “words” take the pulse of “the sufferings of the times”:

Riddim line vessel im ache

from im heart outside

Culture carry im past

an steady im mind

Man take a draw and feeling time

Words cut harsh and try to find

explanations for the sufferings of the times

Oh Lawd, Oh Lawd, Oh Lawd, eh ya….

Is a long time we sweating here

Is a long time we waiting here

to join society’s rites….

DJ chant out, cutting it wild

Say man hafti dub it inna different style

When doors close down on society’s rites

Windows will prey open

In the middle of the night….

Listening to this recording, I hear resonances of a reoccurring narrative taking place at Regent Park. During the 1940s, the displacement of Irish neighbours of Cabbagetown within an English-dominated city was echoed in 2003 — when Toronto City Council approved the revitalization of Regent Park — by the displacement of racialized working-class neighbours by new residents in an intensely gentrifying city.

True, these days we no longer adopt the language of “slum clearance”; it is now replaced by a language of “mixed-income neighbourhoods”. The vocabulary of “revitalization” and “public–private partnership” serves as a substitute for that of “urban renewal” and “public housing”.

But the end result remains the same: narratives legitimize the rights of certain people to certain places, precisely by invalidating the rights of other people to those same places. The roots of this storyline are, I think, deeply colonial.

The repetition of this refrain helps, in part, to explain the sufferings of this city I call home. Lillian Allen’s work—and its call to “dub it inna different style”—provides other resonances to narrate other plot lines: windows prying open at moments when doors get slammed shut.