On July 1st, 2017, I had the following dream:

“I dreamt I was at a long table in the woods with women from different nations across Turtle Island. Each woman introduced herself in her native tongue and as they spoke the AV [auditory-visual] synesthesia I experience in my mind’s eye became projected before me and hovered over the centre of the table. The colour, shape and texture of the image would shift in tandem with the rhythm and timbre of speech, like a map of territory over time. When it came my turn, I found that my tongue was frozen and my mouth ached for sound.”

In her essay “Through Iskigamizigan (The Sugar Bush): A Poetics of Decolonization.” Poet Waaseyaa’sin Christine Sy notes that “Anishinaabe peoples obtain knowledges from multiple sources and methods: observations, reflections, intuition, sleeping, ceremonies, fasting, and dreaming.” In seeing the validity of dream knowledge Sy “accept[ed] certain paths presented to [her] through dreamtime” such as the insight she was shown through paawaanhije (dream) in her relation to the iskigamizigan (sugar bush), particularly regarding “the feminine forces of the sugar bush and the gendered nature of the work.”

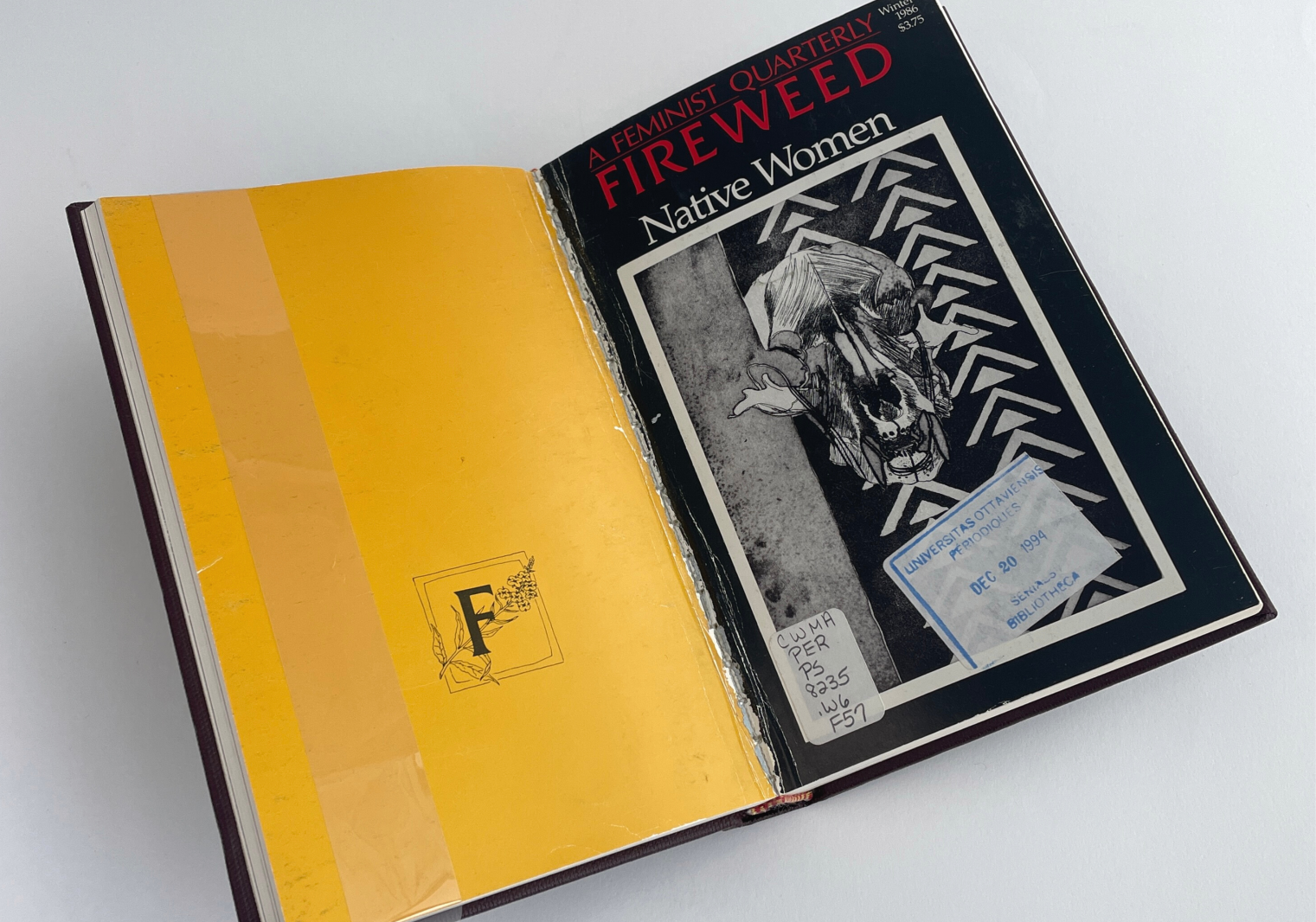

Having been given the task of generating a creative response to Fireweed 22 (1986) “Native Women,” an offering which contains the voices of more than 31 women from over 20 different nations across Turtle Island, I recognized the importance and instruction of my dream. Over the past five months I have been dreaming alongside this text and this text has become a kind of dreaming. A place where borders dissolve. A polyvocal dream song. A borderless sonic geography.

“Native Women” arrived in the form of a scanned pdf. Its first page displays Fireweed’s logo, a capital F on top of the titular flower in illustration. A definition follows:

“fire•weed n : a hardy perennial so called because it is the first growth to reappear in fire-scarred areas; a troublesome weed which spreads like wildfire invading clearings, bomb-sites, waste land and other disturbed areas”

I know fireweed as an organism of secondary succession. Secondary succession is an ecological process whereby organisms grow and thrive in areas disturbed by external forces such as fire, insect invasion, landslide, or human activity. The deep pink beauty of fireweed is a beauty born of disaster.

There is a field of fireweed behind my cousin’s home in Biigtigong Nishnaabeg, a reserve on the northern shore of Lake Superior. My grandmother’s niece, I visited her for the first time this past summer. Like myself she is no stranger to estrangement and welcomed me openly. She asked me to take her picture out on the deck that overlooks the fireweed. It strikes me now that she is of the same generation of many of the women published in “Native Women.” When she shared her stories with me, I knew I had been entrusted to preserve her words and carry them forward within me. Knowledge as connection survives and propagates.

“Native Women” was curated by a guest collective of editors: Ivy Chaske, Connie Fife, Jan Champagne, Edna King and Midnight Sun. Their opening editorials spoke to the reality of Indigenous women’s writing as being “unheard, silenced and invalidated,” that their task was to continue to share and celebrate the life and work of Indigenous women, and that they refused to be bounded by nor defined by colonial strictures, especially the geographical boundaries of nation-states. The voices and nationhood of the issue’s authors transcend the false, imposed border between the lands called Canada and the United States.

Dreaming is also a place where borders fall away. In Western science the brain activity associated with REM sleep, the period of sleep most associated with dreaming, is indistinguishable from the waking state. One theory regarding the discursive nature of dreams offers that dreaming is the by-product the activation, recombination, and synthetic consolidation of old and new sensory data towards the formation of long-term memories. For Anishinabeg, dreaming brings us into the realm of mnidoo, spirit or mystery, where knowledge and songs can be revealed. Anishinaabe philosopher Dolleen Tisawii’ashii Manning has stated that she “…undertake[s] mnidoo-worlding to be an unconscious conceding or an interruption of intentions that is embedded over generations.”

My dream could be seen as a manifestation of generational processes conducted through the orchestra of mnidoo intelligence. By rendering these processes explicit through my own embodiment (voice, curation, and inscription) I enact a dream song.

In her article “Traditional Native Poetry,” Dr. Agnes Grant provides an account of the nature and importance of dream songs:

“Songs which served as tribal conductor of dream powers are found universally. In dreams spiritual powers spoke to the tribal members, giving their daily lives contact with the sacred through awareness heightened by dreams. Supernatural elements could be dealt with through dreams; dreams could also be medicinal or therapeutic leading to personal well-being through contact with forces beyond human limitations. Songs appearing in dreams and visions might cover any aspect of life and usually remained personal and private property. Dream songs were the most precious personal possessions of the individual, often having been received only after suffering and loneliness. The obligations of the dream were as binding as the necessity to fulfill a vow but a person might go a lifetime without fully understanding the dream.”

KWEWAG DREAMING is a dream song of generationally embedded desire lines, a topography of sound, and a humble offering among the secondary succession of Native women’s voices as we continue to thrive and create within the disturbed earth of colonialism.

This is kwe as method. As Anishinaabe author Leanne Betasamosake Simpson has written: “… kwe as method is about refusal … I exist as a kwe because of the refusal of countless generations to disappear from the north shore of Lake Ontario.” It is my hope that this work carries the spirit of the editorial collective’s refusal of a Canadian literature that subjects the voices of Indigenous women to erasure.

Kwe is Anishinaabemowin for “woman” and kwewag is its plural form, “women.” In this creative response piece I have gathered material from each poem, story, essay, and report in “Native Women” on the basis of successive queried readings. I queried the texts for references to embodiment, land, colonized experience, traditional knowledge, time, cosmos (dreams, spirit, and sky), as well as first-person and collective (“we”) statements among others. I have recombined the voices of these Indigenous women authors into a dynamic geography of sound—a way of bringing my 2017 dream into our shared reality. Each line or set of lines will contain its author attribution on the right-hand side. The piece begins and ends in the same way as the magazine issue, with poems by Marcie Rendon. The song has three movements and a “Contributor Notes” section which pulls material from the biography of each author (tribal affiliation, location, and a sample line) as well as a quote from their work in the issue. This ensures that each voice is represented.

i am woman. i have been

torn from my roots and the seeds

of my being strewn

across the countryside. i

have replanted my soul and

am struggling to break

ground. i have pulled

together my life giving

forces and am nurturing them

in the glow of the first

quarter moon

—Marcie Rendon

Click on the Issuu reader below to read the full text of Liz Howard

Listen to the recording of the event Desire Lines. Poetry reading with Liz Howard on February 25, 2023 at Artexte.