Artexte For your residency project here at Artexte, you explore text and audio description in art from an intersectional approach. Can you tell us what led you to this area of research? And what made you want to revisit the idea of “description” in the art context?

Marie Samuel Levasseur I actually came to audio description and text description separately, via different paths. The broader point of departure was my research-creation practice, where I was developing a methodology I call bavardage (chatter)—a way of making art that draws on multiplicity and micro-narratives. For me, description isn’t just about translating or explaining; it’s an act of presence, an act of relationship.

But it was really my own personal experience as a caregiver that led me to specifically revisit the idea of description as such. I care for my child, who has encephalopathy and severe receptive and expressive speech disorder, among other things. So, every day in my role as a caregiver, I describe the world to them. Through this experience, I have come to understand that to describe is to love. It means building something together, making the world livable for someone else, and in doing so, allowing oneself to be transformed.

In the art context, it seems to me that description has often been thought of as a practical, technical, and neutral activity. However, in reality, description is never neutral: it carries subjectivity, a voice, a situated perspective. This is precisely what interests me: how audio and text description can become sensitive, porous, intersectional practices; how multiplicity can lead to much greater precision than traditional methods based on reduction, synthesis, and concision.

A few years ago, during a residency (Interroger l’accès) with Oboro, the MAC, and Spectrum Productions, I tried to reframe the idea of audio description so it would no longer be seen as a mere afterthought, a layer added at the end of a project. Instead, I proposed that description is a space of creation in its own right—a space of care, resistance, and hospitality. For me, it’s also a political question: Who has access to the artwork? With what words? With whose voices? Who narrates? Who translates? And who is it for?

It is with these questions, which are theoretical, but also deeply emotional and rooted in the everyday, that I wish to open this research project at Artexte.

Artexte Can you tell us more about your “méthodologie du bavardage” (chatter methodology)? Where does it come from? How does it manifest itself concretely in your practice?

Marie Samuel Levasseur My practice is based in chatter because chatter firmly rejects finality and repetition. It allows me the possibility of always telling a story differently, of always starting over again without aiming for a coherent ending. The chattering person—the so-called chatterbox—is often perceived as excessive or bothersome. However, the chatterbox possesses a particular form of knowledge: they reveal, they shed light, they know secrets. Their words, judged to be too verbose, too dangerous, or too disordered, circulate every which-way, avoiding linearity and narrative closure.

Writer Suzanne Lamy (in D’elles, published by L’Hexagone in 1979) describes chatter as a “a window, a wound, a valve, an escape, an outlet”, that is, a path of exploration and self-revelation. She also writes that chatter is often considered “irredeemable” discourse, because it does not allow itself to be confined to a goal. I feel that my own place is precisely in this absence of finality. Perhaps because I find comfort and a form of hope there as well.

My experiments with the unspeakable—the inexpressible, with what is not supposed to be said out loud in social spaces—seek to thwart normative language. Through the proliferation of voices, through the breakdown of time and memory, through fragmentation and multiplicity, chatter becomes a form of resistance.

Chatter also means making do, tinkering and creating with that which remains. After loss, destruction, and trauma, what is left? How can we make something out of it? The chatterbox, much like the tinkerer, works with the vestiges. She assembles, cuts, glues back together, stitches up, creatively misuses. She makes these vestiges into something material, something new, she transforms it into living narrative. Detritus and noise, like silence and unspoken words, also tell our stories. And out of them, other forms of memory and meaning can emerge. I am a chatterbox; it is my way of speaking, of thinking, of creating. It is my way of making meaning.

Artexte While exploring the Artexte collection, were there any documents, formats or voices that particularly moved you? Were there specific moments of surprise or resonance during your research and readings?

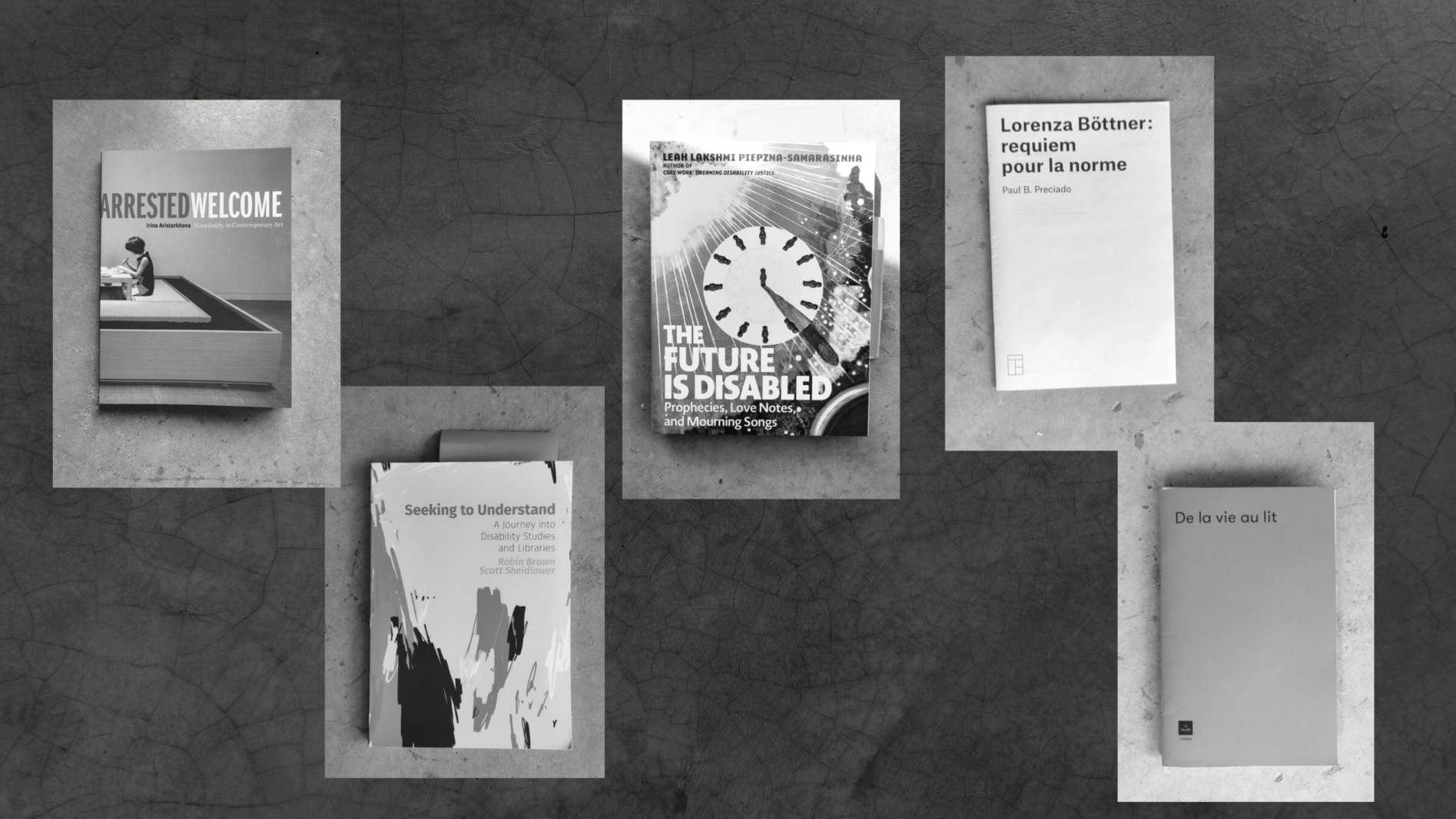

Marie Samuel Levasseur As a true chatterbox, it wasn’t one specific voice, but rather the multiplicity of voices that most moved me during my research at Artexte. I find libraries and archives moving because of the thousands of voices that meet there, defying eras and geographic constraints. For example, I was able to make connections between the exceptional practice of Lorenza Böttner, a Chilean-German trans artist from the 70s-80s who worked with the handicap of not having arms, and the recent writings of Amanda Cachia on prosthetics in contemporary art. What a privilege it is to have text, audio and video traces of these artists, knowing that only a tiny part of crip knowledge is considered and conserved by institutions. I can only feel sadness when I think of all the people who have been erased from the monolithic History told by the privileged in libraries and schools. Fortunately, oral history and other subterranean modes of recounting have allowed some otherwise inaudible voices to survive. I hope to be able to further develop the files of Indigenous artists and d/Deaf and disabled artists in the Artexte collection over the coming years.

Artexte You posit a vision of description that touches on the essence of the relationship to the work, to oneself, and to others. What would you like the art world to take from this approach?

Marie Samuel Levasseur What I’d like to get across, very humbly, is that description is not just a secondary or peripheral operation, but rather that it touches on the essence of our relationship to the artwork, and even goes through and beyond it. This essence is not a monolithic truth or an objective meaning that must be faithfully translated; it embodies the depth of the experience: the encounter between body, subjectivity and artwork, with all the affects, contexts and resonances this entails.

In working on this bibliography, I’ve tried to pay particular attention to how artists from equality-seeking communities describe their own artworks. Their modes of description often circumvent or reject the idea that there is a single “right” or “complete” way of speaking. Instead, they embrace micro-narratives, the craft of detour and circular forms. These strategies open up the possibility of description that eschews exhaustivity in favour of embodiment.

These practices should not be seen as technical or anecdotal add-ons, but rather as forms of knowledge in their own right. They show that description can be polyphonic, that it can incorporate multiple, situated, and even sometimes contradictory voices. And this polyphony—far from diluting the aesthetic experience—reveals the layers, the gray areas, the possibilities carried by the works themselves, by the artists, and by their own spaces and systems of creation and dissemination.

For someone like me, who has worked in the museum and communications fields for nearly 15 years, revisiting description is not just about improving accessibility in the technical sense of the word. It’s also about questioning the way language shapes our relationships with artworks, and indeed the world. It’s about asking: Who’s allowed to speak? Which bodies? Which voices? Which experiences are considered legitimate in art spaces? By foregrounding these questions, description becomes a tool for symbolic redistribution: it can contribute to transforming and making visible. In short, description is not an extra or an afterthought, but a critical, situated, and sensitive practice that encourages us to rethink our frameworks of production, mediation, and transmission. Describing an artwork is a way of giving voice; of centring the Other. It’s a way to position oneself as an active witness.

Artexte You draw inspiration from crip practices in order to think differently about description. What do these approaches allow us to repair or reinvent, in our relationship with art and accessibility?

Marie Samuel Levasseur Both as an artist and as a caregiver, crip studies and the practices of disabled artists offer me the hope that we really can build new models and generate new forms of knowledge and activism, with the goal of changing our world and its oppressive structures. I am not a defeatist, perhaps because I consider myself a survivor. And I’ve survived thanks to models of interdependency, because the disabled people around me are a source of deep beauty and joy, and because they choose to live their lives to the fullest. Much like Indigenous forms of knowledge, Crip practices debunk myths of efficiency and linearity. They demonstrate the benefits of other rhythms, other languages, and other ways of building community.

Description enables us to repair many things. Firstly, the feeling of exclusion that art provokes when it is designed for a supposedly homogeneous audience. Crip practises recenter experiences that are usually marginalized. They challenge the idea that these experiences represent a kind of lack, and affirm their role as vectors of situated knowledge and lasting solutions for the future of our world. They show that we can describe using many voices, with humour, poetry, and subjectivity. That we can slow down, digress, improvise, be comfortable, and leave room for uncertainty. They allow us to reinvent our relationship with accessibility itself: not as an afterthought or a kind of repair, but as rather as a driving force for creation. They remind us that making art accessible is not about standardizing, but rather about multiplying possibility.

Crip practices expand how and what art can be, and for who. This is why I advocate for more funding, space, resources, and consideration for d/Deaf and disabled artists and publics. My d/Deaf, disabled and Indigenous friends are extraordinary people, artists, and researchers, and I dream of a future led by them. It is this idea that gives me hope and keeps me going.