Kaysie Hawke When you started this research residency, Kristen, you were invested in surveying work by Canadian lesbian and queer artists from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, who are often underrepresented within art collections and archives. Could you expand on your choice to focus on these particular decades and what brought you to Artexte?

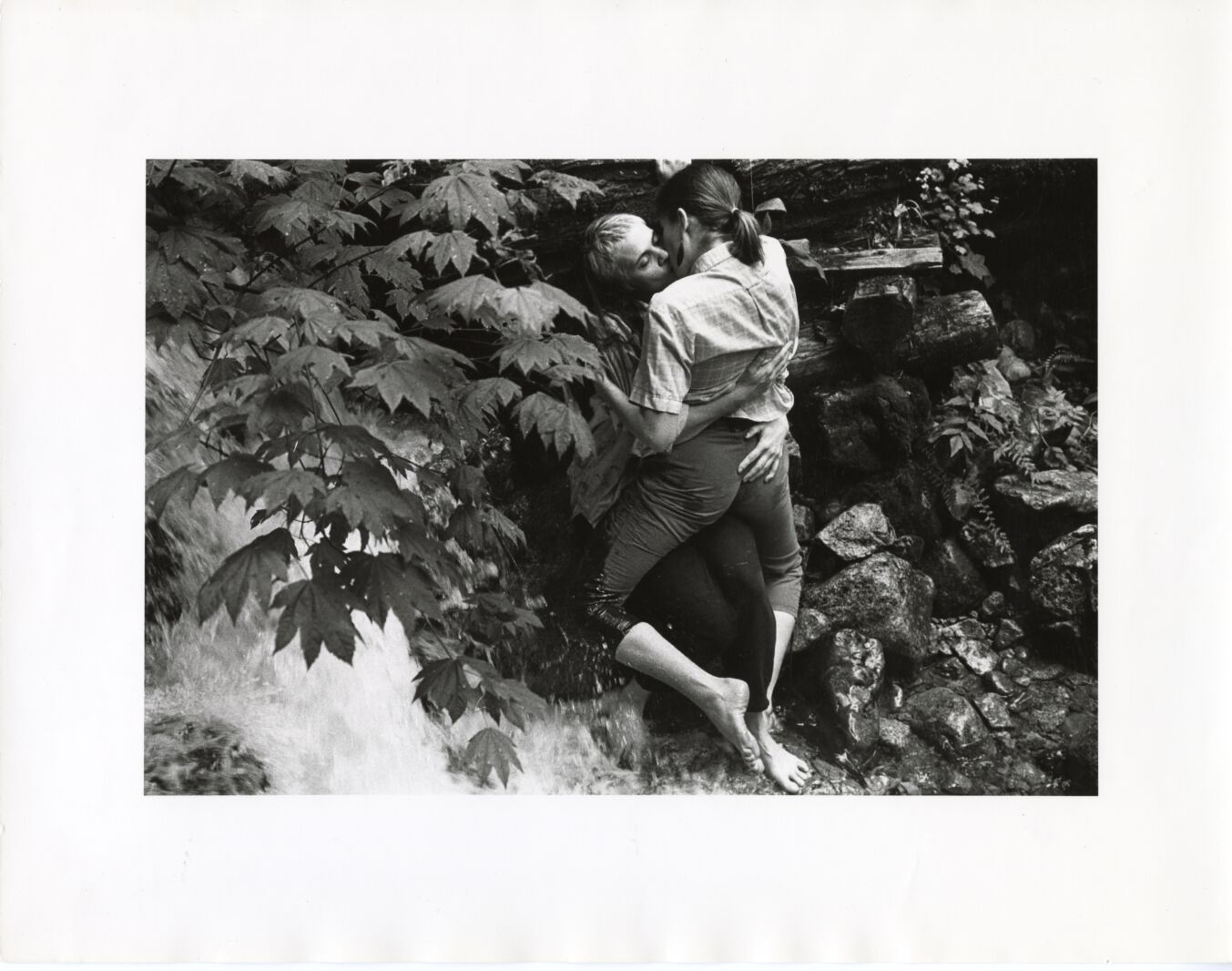

Kristen Hutchinson My research at Artexte is an expansion of work I have done about the Vancouver lesbian art collective Kiss & Tell, who created exhibitions, books, and performances about censorship, lesbian bodies and representation, disability, art as activism, and the feminist sex wars from 1988 to 2002. The collective created spaces where women could see themselves represented in visual culture through a queer female gaze in ways that had yet to be seen in the Canadian art scene. I have recently written a book, titled Kiss & Tell: Lesbian Art & Activism, that will be available as an open access, online publication by the Art Canada Institute in June 2025. [1] During my research about Kiss & Tell, I realized how little has been written about Canadian lesboqueer artists, particularly during this period, and applied to do a residency at Artexte to discover more about these artists.

Kaysie As part of your research, you’re interested in cases of censorship that occurred at that time, such as discriminatory practices enacted by Canada Customs and police raids on queer events that happened in Montreal and Toronto. Are there any parallels to be made with our current political landscape and have you gained any perspective on this aspect from your research?

Kristen Given the recent backlash against LGBTQ2S+ people in Canada and the U.S., queer visibility through nuanced and affirming representations and knowledge of our Canadian queer activist histories is more important than ever. Much of this backlash and legislation is targeting queer, especially trans, youth who should be able to use whatever pronoun they want and to feel safe in their schools. It is hard for all kids to process whatever their sexuality might be, and it is certainly much harder when you are queer and under attack. This hatred toward LGBTQ2S+ youth is especially troubling since they already have suicide rates higher than most populations.

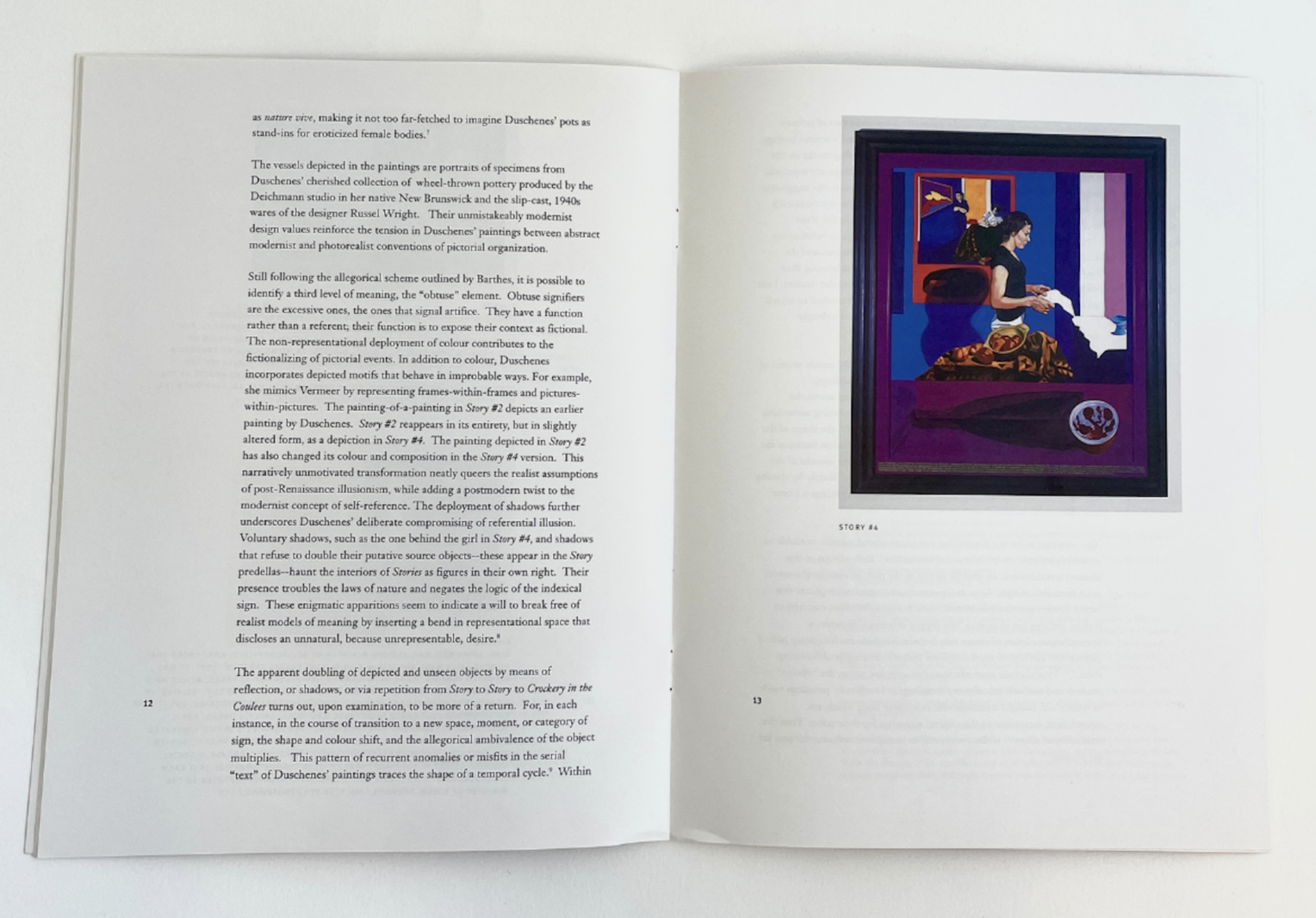

The current anti-queer legislations, increased violence, and spread of misinformation feels like a return to the homophobia propagated against, and experienced by, queer people during the 1980s and 1990s, especially during the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. We can learn a lot from the queer artists and activists of that era, who used art, performance, journalism, protests, and writing to fight back against discrimination. For example, Canadian artist Julie Duschenes’s series of paintings titled Stories That Own Me (1996–2000) focused on lesbian domestic life and legalized homophobia. In Story #4, a woman is in the process of tearing apart the fabric of her home, while in the background we see a painting of two women within another domestic space. The caption in the exhibition catalogue reads: “1996: Stockwell Day, Alberta Minister of Social Services, announced that homosexuals were not eligible to become foster parents.” [2] Duschenes drew attention to the lack of equal rights for queer people in Canada at the time, which is, infuriatingly, happening again with legislation such as the three anti-queer laws recently passed in December 2024, in Alberta. [3] We need to remain vigilant to make sure these kinds of laws do not happen in other provinces and federally, and looking back to how queer activists protested and rebelled against homophobia before is a good place to start.

Kaysie Have you uncovered any new threads to your research through your time in the collection?

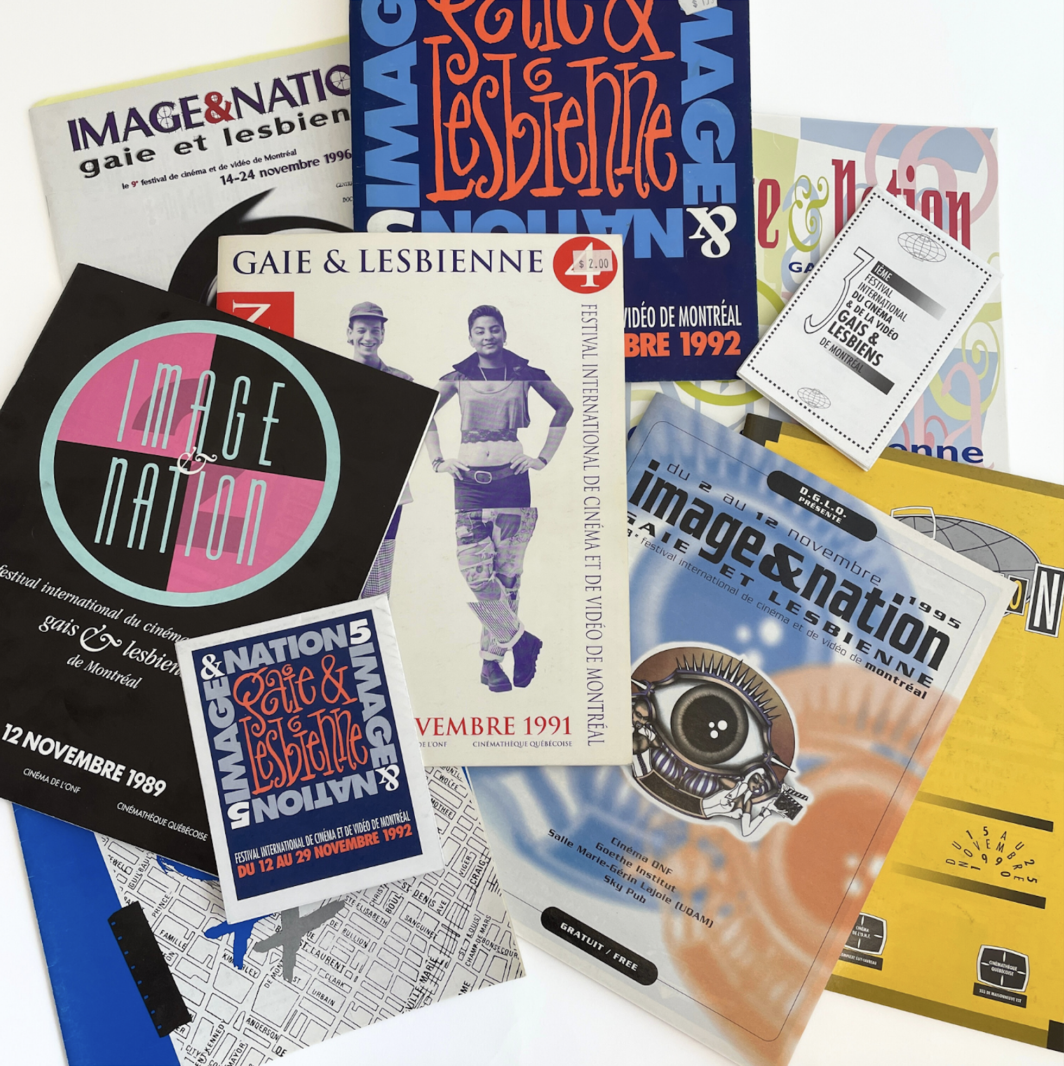

Kristen I have discovered a prolific history of Canadian lesboqueer video art that I knew existed, but was unaware of just how often the medium was used in the 1980s and ’90s to celebrate lesbian and queer identities, and as a tool for activism and experimentation. The videos are scattered throughout Canada’s media art organizations’ and artist-run centres’ collections. For example, the 1990 documentary We’re Here, We’re Queer, We’re Fabulous, by Maureen Bradley and Danielle Comeau, can be found in the Groupe Intervention Vidéo (GIV) archive. The description reads: “Sexgarage was a warehouse party crashed by Montréal cops in July 1990. In the wake of the unnecessary brutality of the police officers, the gay and lesbian community(ies) undertook a series of actions. Their peaceful means were met with more violence and massive arrests. This tape is a chronological look at the events, including a huge march/celebration.” [4] Videos like these are important documents of queer activism in Canada that need to be seen. By looking through the program booklets at Artexte for the annual Montreal Image+Nation: Festival Film LGBT2SQueer (1987–present), I was able to discover many lesboqueer short video-art and film gems I had never heard of before. My research at Artexte about Canadian lesboqueer video art will result in a screening of short films such as Melina Young and Sheila James’s Lakme Takes Flight (2001), from the GIV archive, in May 2025. I also hope to create a feature-length documentary on the topic to ensure these artists and their video art receives greater attention and distribution.

Kaysie Often, when researching at Artexte, methodologies tend to shift and adjust depending on what is found and, often, on what is not found. I’m curious to return to the beginning: what were your first insights as you delved into the collection and how did your approach evolve as you dug deeper into the boxes and documents?

Kristen It was such a delight to pull boxes off the shelves and shuffle through papers, exhibition catalogues, news articles, postcards, ephemera, etc. I discovered the names of many Canadian lesboqueer artists that I had yet to be aware of and found new information about artists I already knew. What I noticed about the lesboqueer artists within the collection, working from 1988 to 2002, is that they are primarily white and English, and that there were many other artists who did not have files at all. I found an older file titled “Art and Homosexuality” that mostly had articles about the American artist Robert Mapplethorpe. Much remains to be done to include more lesboqueer artists, especially women and non-binary people of colour and Québécois artists, within the collection. My approach shifted to not only discovering new artists but also to thinking about how to increase lesboqueer visibility within the Artexte collection. With this in mind, through my exhibition at Artexte I will be encouraging queer artists to make their own files (using Artexte’s submission parameters) to secure their place within the canons of Canadian art history for generations to come.

Kaysie Artexte will indeed have the privilege of welcoming your work once again in the spring with an exhibition stemming from your research in the collection. Do you have any key words or thoughts to share with our readers on this upcoming project?

My current plan is to transform the white cube of the gallery into a cozy space where people can come, take off their shoes, turn off their phones, relax, and peruse the many types of publications and documents about Canadian lesboqueer artists I have found in the Artexte collection, look at posters from the Archives Lesbiennes du Québec, and connect with others. Queer artists will be encouraged to bring documents to create their own files. I will also be launching my online, open access book Kiss & Tell: Lesbian Art & Activism at the finissage of the exhibition and curating a screening, at Groupe Intervention Vidéo, of Canadian lesboqueer short films and video art from their archives.

Kristen Hutchinson’s exhibition will take place from April 18 to June 21, 2025, in Artexte’s gallery space.

Kaysie Hawke has been the programming coordinator at Artexte since 2023. She holds a master’s degree in aesthetics and philosophy of art from Université Paris-Sorbonne IV, as well as a bachelor’s degree in art history from Université du Québec à Montréal.