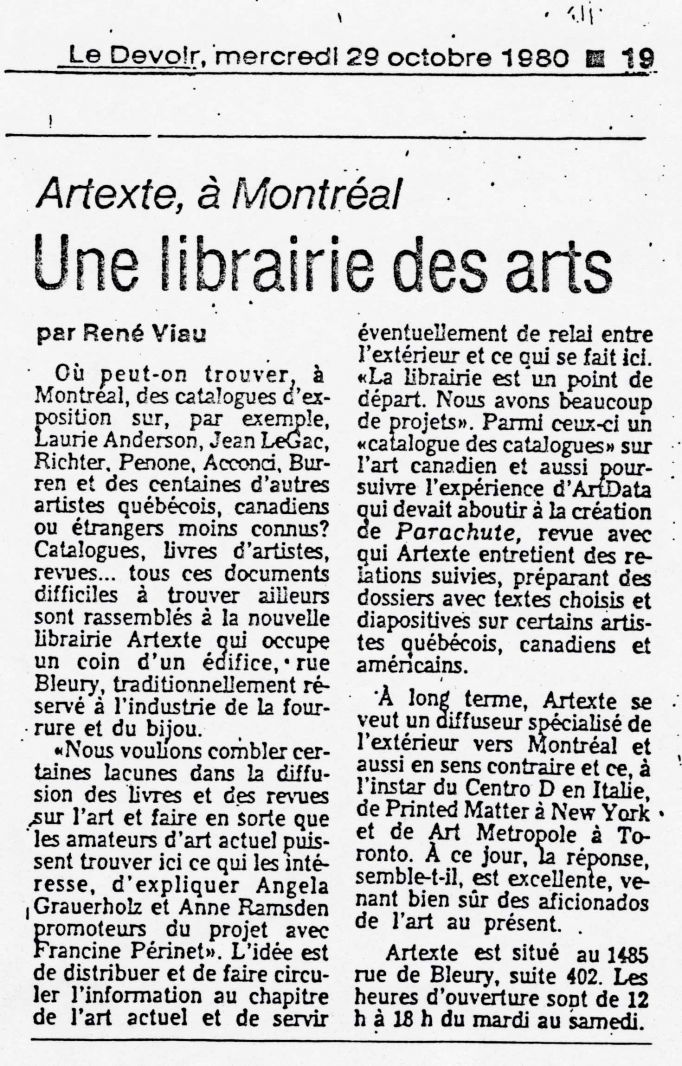

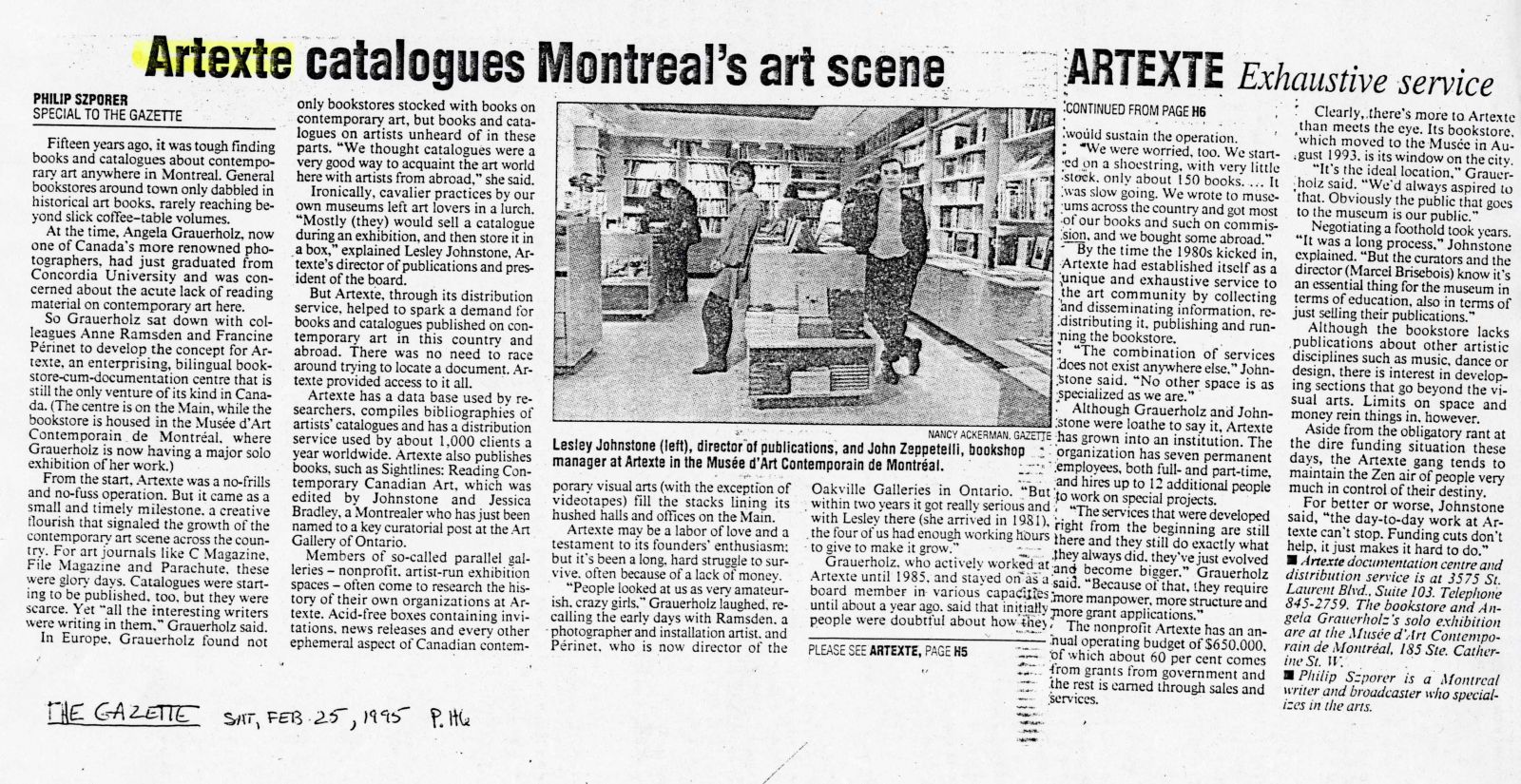

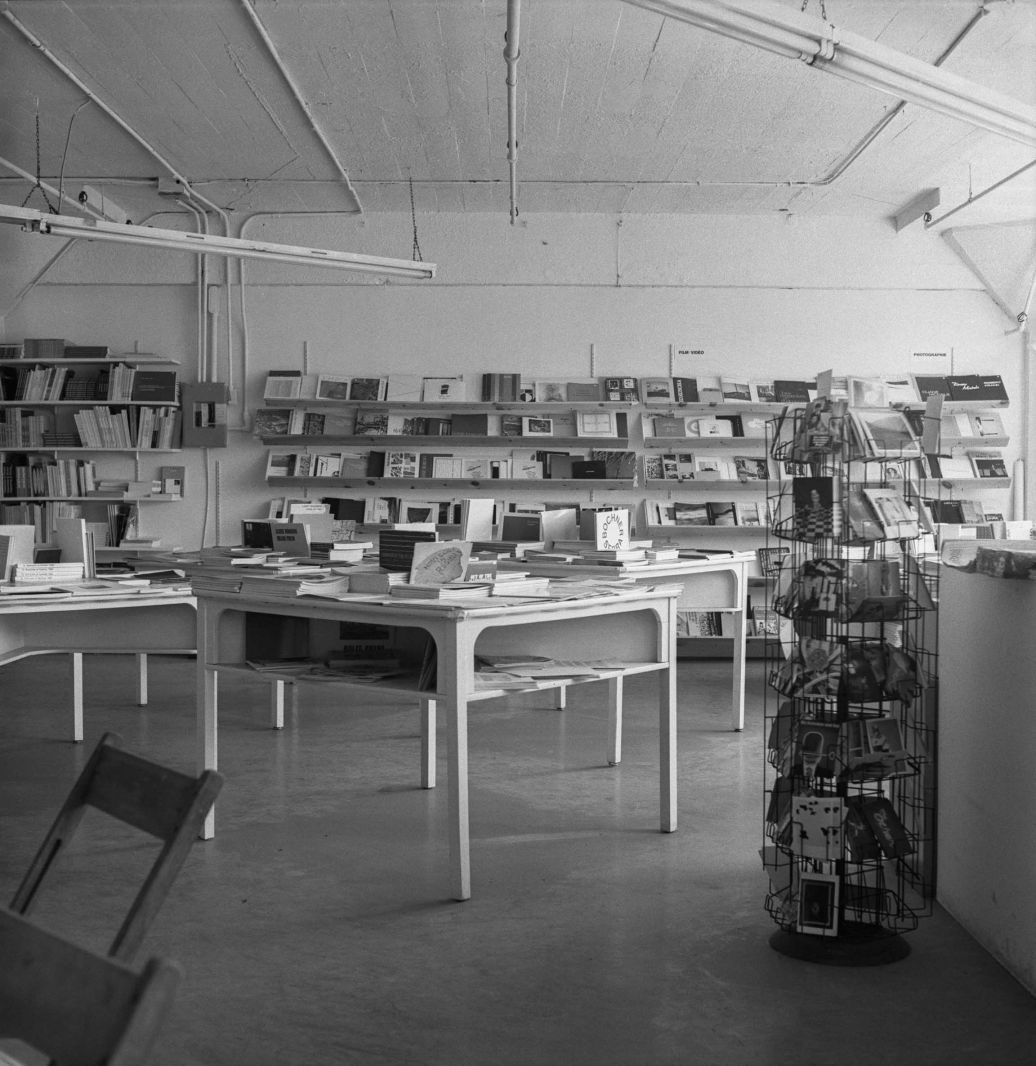

Founded in 1980 by artists Angela Grauerholz and Anne Ramsden and art historian Francine Périnet, Artexte was created as a response to a growing need in the arts community to access publications on contemporary art which were previously not available in Canada.[1] During the same period, Librarian of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Clive Phillpot wrote an article advocating for the importance of the art library to adopt an “inclusive, social role” by giving access to visual information and art documentation, which are valuable forms of “visual nourishment” and inspiration.[2] With similar ideas in mind and a mandate of service to the public and the community,[3] over the years Artexte has acted as a specialized bookstore, a distributor, a publisher, a documentation centre and a cutting edge open-access digital repository (e-artexte). Now, it also serves as an artistic think-tank with its exhibition space and research residencies.

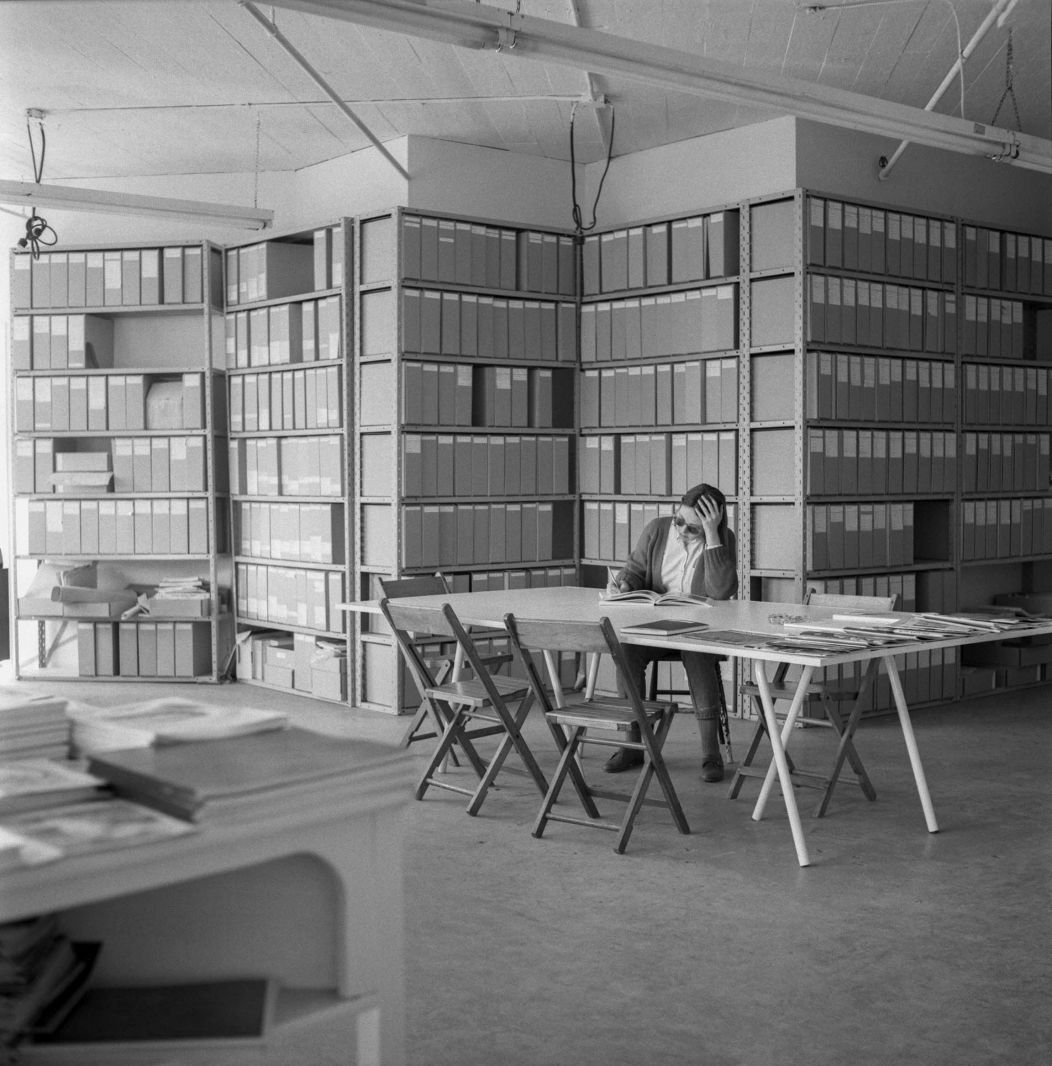

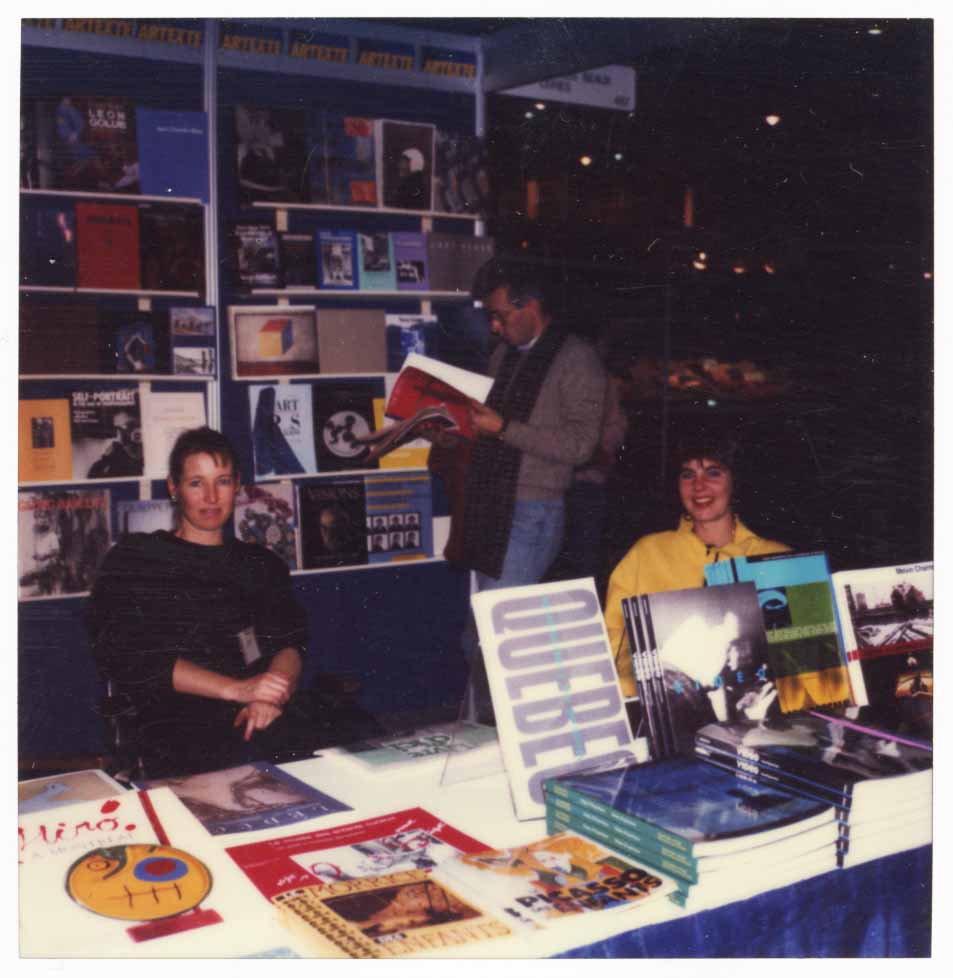

During the 1980s and early 1990s, the distribution service, Artexte Editions and bookstore were all factors that helped to create ideal conditions to build the library collection and a robust pan-Canadian network of artists and organizations who became accustomed to depositing their documentation and publications. In addition, documentation included not only publications but also various ephemera for example, flyers, pamphlets and posters. Often these documents represent smaller, more obscure exhibitions, which are an important, and often neglected, part of Canadian Art History. The documentation of these smaller exhibitions can be hard to find for researchers in traditional libraries, but much of it can be found in the files of art organizations and artist files at Artexte. [1] Researchers use the collection for traditional and non-traditional expressions of both intensive research and intuitive browsing. Art history students, researchers and professors use the collection primarily for information purposes, and artists use the collection for inspiration and material for the creative process.

Considering our history, we have to ask ourselves, what is included in art documentation, and what is left out? How can we capture a diversity of artistic practices from a broad community and identify what will be important in the years to come? These are questions we continually ask ourselves at Artexte, and although the answers to these questions have certainly varied and changed over the years, there is one guiding principle that remains unchanged: the art library is not a passive entity that merely solidifies past artistic productions; rather, its materials are part of a fluid dialogue of the present.

We can consider Artexte as a repository for histories, yet we must recognize that histories are not fixed in the collection—they are continually reinterpreted and constantly evolving.[1] Through the cycle of research and creation, new meanings are found and new connections are made between artists and ideas alongside changes in cultural consciousness.

Ideas travel through documents to the hands and minds of individuals through their interactions with the collection. In this way, narratives that were historically ignored or misrepresented in Canadian art history can be revealed.

Research often serves as powerful vehicle for new ways of seeing and interpreting art history through the collection. Two recent examples include the projects: An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time: Performance Art in Quebec and Canada. An extensive bibliographic survey of writings, publications and printed matter on Quebec and Canadian performance art since the 1950s, as part of a long-term university research project under the direction of Barbara Clausen (UQÀM).[1] Also, in 2015, a research residency with the Ethnocultural Art History Research Group (EAHR) focused on identifying and drawing attention to the work of Black Canadian and Asian Canadian artists in Artexte’s collection.[2] The project shed light on the lack of representation of these two groups in Canadian art institutions, and also revealed a richness of artistic practices, providing an opening to these histories and a way of making them findable for future researchers.[3]

In this way, we see how research can open dialogues— the simple act of making information available can benefit a larger community in a myriad of ways. In the accompanying publication, Uncovering Asian Canadian and Black Canadian Artistic Production, EAHR states “The research and exhibition of these documents are EAHR’s small contribution to an ongoing, larger narrative of resistance.”[1]

Like any library in the 21st century, the shift in information culture and technology has made it necessary for Artexte to look critically at its methods of collecting and disseminating information and reevaluate how we can best serve our public. How can we offer something that is unique in this era of individual online searching? How can the art library contribute to the arts community and to society as a whole?

In the early 1990s, Simon Ford introduced the concept of “New Art Librarianship” in response to ideas around the “New Art History”, which didn’t simply look at art, but critically evaluated the social and political conditions of artistic production. Ford describes the necessity for art libraries to evolve and question issues of authority around the production of knowledge, and to re-examine their methods of acquiring and organizing information and making it accessible. [1] Now, more than 20 years later, we remain in a paradigm that requires us to consider how we can continue to be relevant in an increasingly digital world.

We often think of contemporary art documentation as being accessible, but in reality this proves not to be the case for a variety of reasons.[1] This issue is complex and presents itself in many different ways. Users of the collection face a number of accessibility barriers. Geographical location, access to art education, and income, for example, can seriously hinder one’s access to contemporary visual art documentation. One of the ways we actively tackle these barriers is through the development of our digital collection and resources. Artexte currently holds more than 1200 digital publications in e-artexte our online open-access digital repository (e-artexte.ca). This is made possible in part by publishers, writers and artists who allow us to distribute digital publications on contemporary visual art to a national and international audience over the internet. In addition to making the digital collection accessible on the web, Artexte is developing a digital education and dissemination program that aims at serving all users who want to acquire knowledge on contemporary visual art, from the advanced researcher, to the artist on a serendipitous quest for inspiration, to the curious art enthusiast.

Going forward, we look to the concept of “embedded librarianship”[1] and envision ourselves in a proactive and anticipatory role[2] by embracing the network, engaging with communities across Canada and forming new relationships. We must continually ask ourselves: what is important to artists, researchers and students, now and in the future?

In the end, supporting artists by preserving and making available documentation on their artistic practice reflects not only the kinds of artworks being produced, but also the relationships between members of the artistic community—a network of connections and collaborations.