The late 1980s and early 1990s were a vibrant period of anti-racism activism in Canada. During this time, a proliferation of exhibitions, conferences, arts festivals, and protests organized by Indigenous, Black Canadian, and Asian Canadian artists and cultural activists challenged the structural racism of Canada’s institutions by engaging with the histories of injustice in public spaces.[1]1Larissa Lai (2014). Slanting I, Imagining We: Asian Canadian Literary Production in the 1980s and 1990s. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 3-4. More than resisting historical and ongoing racism, these activities called into question the cultural politics of representation; specifically, what Monika Kin Gagnon has identified as the dynamics of “visibility, visuality, and power,” which establish “who defines and determines cultural value.”[2]2Monika Kin Gagnon (2000). Other Conundrums : Race, Culture, and Canadian Art. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 23. Artists unsettled the terms of cultural belonging tied to the framework official multiculturalism, which identifies difference while also flattening it. They not only sought to make visible the erased effects of exclusion, racialization, and colonialism, but also aimed to contribute to the formation of aesthetic subjectivities on their own terms.

As a field of study, Asian Canadian contemporary art has in part developed through the creative practices of artists and cultural producers who helped galvanize anti-racism activism from within and across Asian diasporic communities. This brief essay examines the intersections between art and activism and how they constitute Asian Canadian contemporary art. I will highlight a few exhibitions that played integral roles in mobilizing Asian Canadian beyond a marker of difference to a form of relation.

The moniker ‘Asian Canadian’ was established in the 1970s when it was imperative to articulate recognizable forms of subjectivity that would combat Asian erasure from all aspects of political and cultural life in Canada. Since then, it has and continues to inform what Roy Miki suggests is a discursive consciousness rather than a stable identity marker.[3]3Roy Miki (2011). Can Asian Adian? Reading Some Signs of Asian Canadian. Edmonton: NeWest Press, 93. Asian Canadian is a political project not without contradictions. It is produced, further, through the complicated entanglements of history; via the relationships between dispersed populations across national boundaries as well as those cultivated within them. On this matter, Christine Kim’s concept of Asian Canadian publics formed through “matters of address, affect, and audience” offers more fluid understandings of diasporic cultural and political identity.[4]4Christine Kim (2016). The Minor Intimacies of Race: Asian Publics in North America. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 18. This idea acknowledges the need for forms of pan-ethnic solidarity (especially in light of current right-wing backlash against transnationalism and ongoing anti-immigrant violence), while also nuancing the relationships between historically racialized and marginalized communities. The exhibitions examined here call into being particular constructions of Asian Canadian identity produced by settler colonial power dynamics and the contingencies of transnational migration.

Desh pardesh is a Hindi expression meaning “home away from home” or “at home abroad.” It is also the name of an innovative, multidisciplinary arts festival organized annually in Toronto between 1988 and 2001. Negotiating forms of cultural belonging and combatting stereotypical portrayals of South Asian cultures in mainstream media, Desh Pardesh provided a platform to raise the voices of those underrepresented within the vast South Asian diaspora and within society at large. It centered the artistic expressions and experiences of members of the diaspora who identified as LGBTQ+, promoting a mandate to foster “lesbian and gay positive, feminist, anti-racist, anti-imperialist, and anti-caste/classist” discourse.[5]5 (). SAVAC (South Asian Visual Arts Centre). Growing out of the context of LGBTQ+ activism in Toronto’s gay village, the festival was “a risky and politically charged place where intersecting diversities and multiple identities collided for the first time; a place where racialized minorities who had until then hovered on the outside edges of progressive social and cultural scenes became groundbreakers, initiating self-determined interventions that resisted exclusion and negotiated social change in the arts.”[6]6Sharon Fernandez (2006). More Than Just an Arts Festival: Communities, Resistance, and the Story of Desh Pardesh. Canadian Journal of Communication, 31.1, 19.

Focusing on the intricate natures of marginalized identities, Desh Pardesh also constituted Asian Canadian contemporary art from multiple transnational positions. The festival explored many geographies and temporalities of ‘South Asian,’ from historical roots in the Indian subcontinent to dispersed populations in Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, the United States and the United Kingdom.[7]7 (2006). Ibid. 18. This multi-directional emphasis signals how identities shift through inter-generational migrations and connections to different homelands. The idea of belonging abroad, coupled with intersections of gender and sexuality, helped redefine Asian Canadian not solely as an opposition to whiteness or heteronormativity. At the nexus of LGBTQ+ and anti-racism activism, Desh Pardesh created a space in which queerness and South Asianness could co-exist and formulate complex understandings of diasporic belonging.

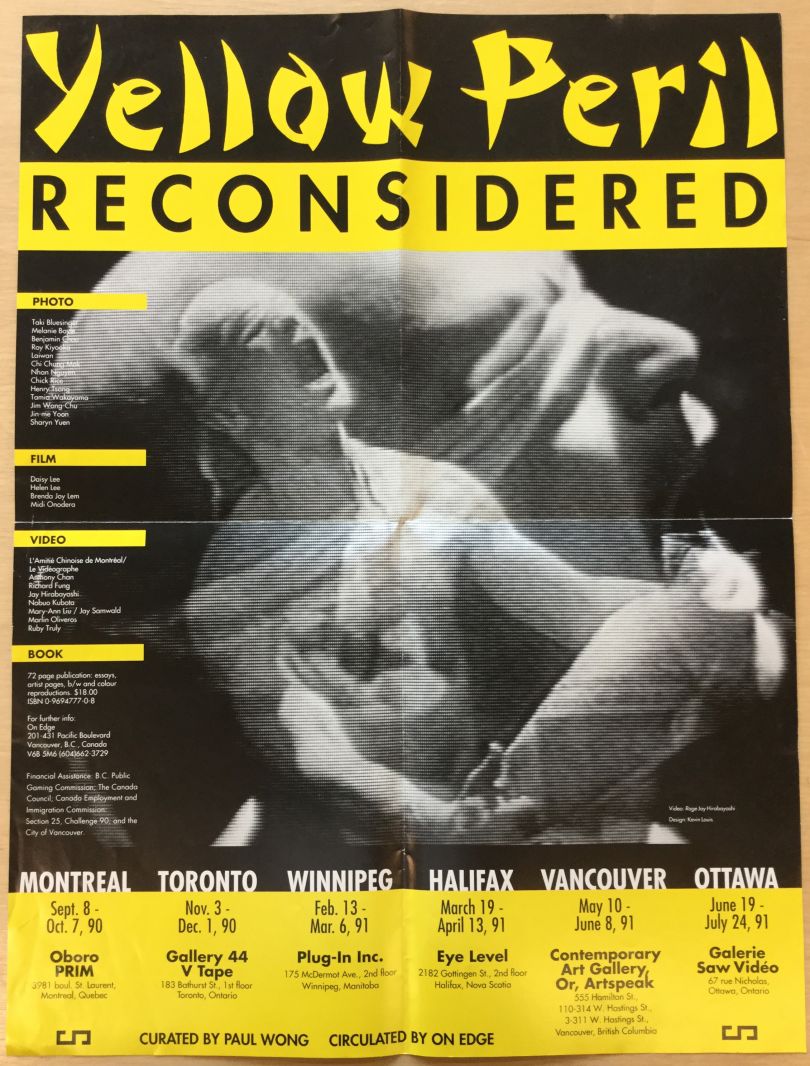

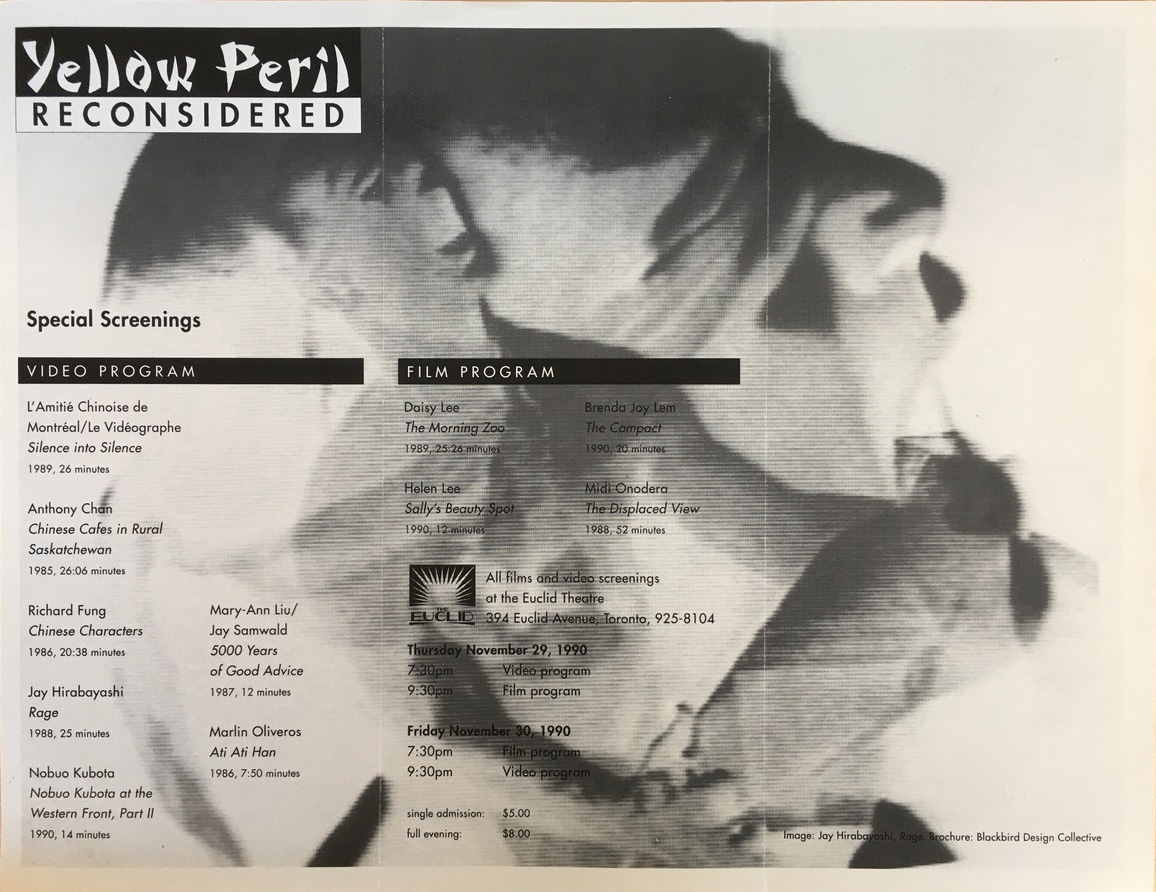

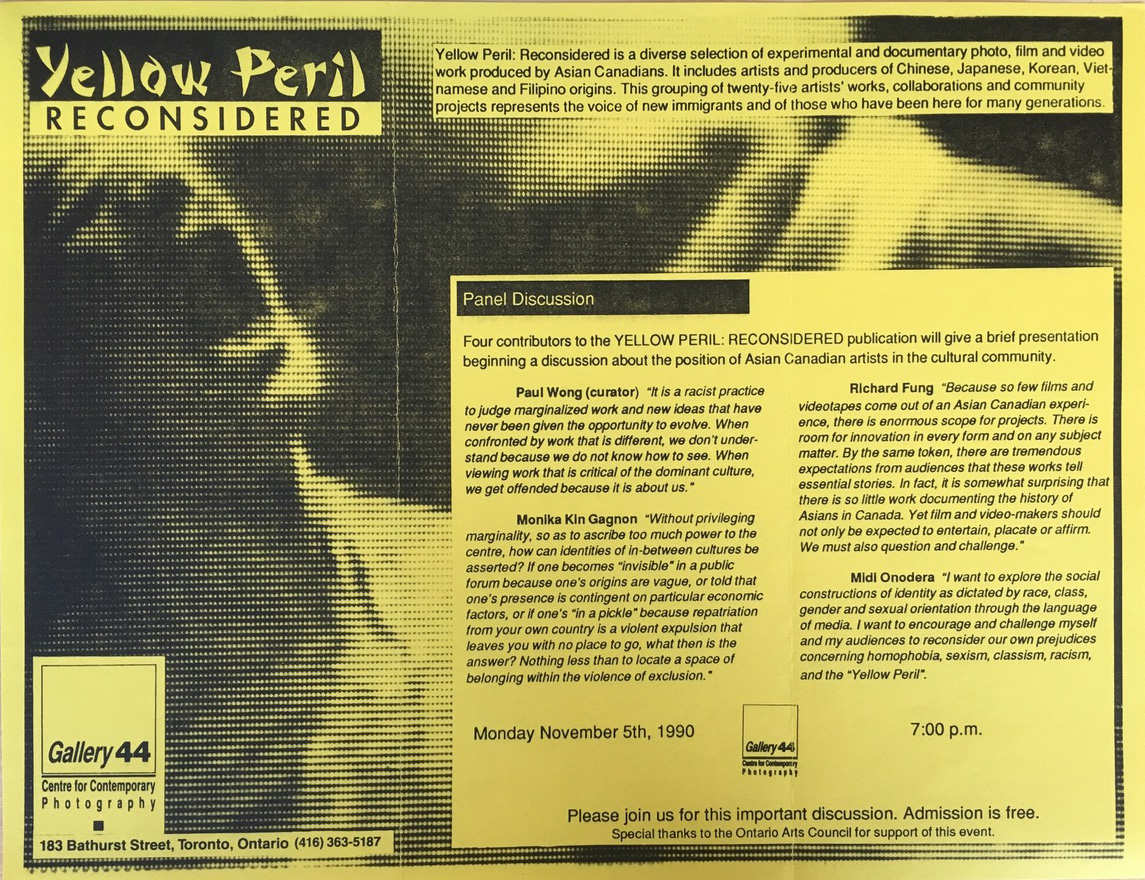

Curated by media artist Paul Wong, Yellow Peril: Reconsidered was one of the first major exhibitions devoted entirely to the works of Asian Canadian artists working in the mediums of photography, video, and film. Throughout 1990 and 1991 the exhibition toured artist-run centres in Halifax, Montréal, Ottawa, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Vancouver, examining historical and contemporary representations of Asian Canadians and highlighting the works of twenty-five artists of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Filipino descent.[8]8 (1990). Yellow Peril: Reconsidered. The intent of the exhibition, and its accompanying catalogue and public programming, was to explore the complexities of establishing a pan-Asian diasporic network; to present critical views by Asian Canadians rather than defining or generalizing Asian Canadian experience.

Though Yellow Peril was produced in conversation with anti-racism activism, the exhibition was critical of how pan-ethnic solidarities could potentially produce Asian Canadian as a monolith. As Wong argues in the exhibition’s catalogue, “Although we are grouped together as one single ‘visible minority,’ the language and cultural problems within our specific ethnic groups are enormous. There is hostility and misunderstanding between native and nonnative borns, the assimilated and the not-so-assimilated, [and between] those whose native tongue is English [and] those whose is not.”[9]9Paul Wong (1990). Yellow Peril: Reconsidered. Vancouver: On Edge, 8. Wong calls attention to the divisions within communities by staging dialogue between recent immigrants and those whose families have lived in Canada for generations. Viewing these dialogues in relation to and in tension with each other, Yellow Peril: Reconsidered was one of the first major exhibitions to trace Asian Canadian through complex histories of arrival, settlement, and political resistance.

Uniting contemporary artists from diverse First Nations, Inuit, and Japanese Canadian communities, Visions of Power was organized via a selection committee as part of the three-day Earth Spirit Festival coordinated by members of these respective communities in collaboration with the Harbourfront Corporation. The exhibition ran from June 28 until July 29, 1991, at the Harbourfront Centre in Toronto. Examining paralleled experiences of cultural erasure, the curatorial theme of “cultural persistence” emerged through the process of jurying works for the exhibition. The theme encompassed issues of “physical survival,” “cultural survival,” and “environmental concerns,” producing critical cross-cultural dialogues. Though the exhibition attempted to find a common ground, it ultimately highlighted the difficulties of working through different sets of cultural knowledge.

Bryce Kanbara’s essay in the exhibition’s catalogue outlines some of these difficulties from the perspective of exhibiting the works of Japanese Canadian artists. He pinpoints a common problem that arises when studying Asian and Asian diasporic art in general: the preconception that the work will maintain aesthetic associations with an Asian homeland. “For most people, the idea of an exhibition of works by artists of Japanese descent evokes immediate recollections of the traditional art of Japan: our fostered impressions of its refinement, meditativeness, and reverence for nature.”[10]10Bryce Kanbara (1991). Looking at Art by Japanese Canadians. Visions of Power: Contemporary Art by First Nations, Inuit, and Japanese Canadians (Toronto: Earth Spirit Festival), 16. Yet, as Kanbara argues, the expectation that Japanese Canadian artists must take up traditional Japanese art practises limits forms of expression, refusing a deeper engagement with Japanese Canadian histories.

The works included in this exhibition highlight a wide range of media from the perspectives of different generations of Japanese Canadian artists. In this regard, Visions of Power follows from earlier exhibitions of Japanese Canadian art, including the Japanese Canadian Centennial Art Exhibition in Ontario (1977; Japanese Canadian Centennial Society and National Gallery of Canada), Shikata Ga Nai: Contemporary Art by Japanese Canadians (1987–1989; Hamilton Artists’ Inc.) and Twelve Nikkei Artists (1987; Powell Street Festival, Vancouver, BC). These exhibitions helped nuance understandings of Japanese Canadian history and identity, addressing the traumas of internment that often resulted in endured silences and shame of one’s heritage. They gave multiple forms to “the violent erasure of self and community that left an empty space, invisible without words, invisible without image.”[11]11 (1991). Roy Miki.

Conclusion

The exhibitions examined above offer a tiny snapshot of Asian Canadian contemporary art as a field of study. Mapping this field requires unpacking particular constructions of Asian Canadian, keeping in mind the historical and socio-political contexts in which they emerged. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Asian Canadian contemporary art was constituted through widespread artist and activist networks that worked to mobilize against systemic racism and colonial violence in Canada. Whereas in the 1970s, the goal was to create a space for Asian Canadian consciousness and to promote the visibility of Asian Canadian communities, in the 1980s and ’90s artists and activists turned toward each other to critique terms of representation. Focusing articulations of Asian Canadian produced through these relations establishes a critical practice that not only measures resistance to racism and exclusion, but also evidences how constructions of Asian Canadian shift through new forms of affiliation.