Flesh itself,

in our ongoing cultural habituation to sight-able remains,

supposedly cannot remain to signify ‘once’ (upon a time).

Even twice won’t fit the consistency of cell replacing cell that is our everyday.

Flesh, that slippery feminine subcutaneousness,

is the tyranny and oily, invisible inked signature of the living.

Flesh of my flesh of my flesh repeats,

even as flesh is that which does not remain.

–Rebecca Schneider

in Performance Remains (2001, p. 104)

Joan Dularge is an alter ego who refuses to accept their ontological fate. Yes, they were born in my imagination, but despite this fact, they keep insisting that they’re real.

And they’re not wrong.

Joan’s existence stems from a decolonial (re)reading of the archive, not as a Western historical practice that defines itself in opposition to the so-called “primitive” subjectivity of body-to-body transmission, but rather as a social performance feedback loop where the document itself is a performative act and thus the site of a body-to-body performance.[1] Indeed, the archive (history via objects) claims superiority over immaterial rituals of historicization—orality, storytelling, dance, visitation, improvisation, etc.—based on an assumed separation from living bodies, considered to be too ephemeral. However, this very archive is impossible without bodies to maintain and circulate it. Simply stated, the archive is merely a whiter, more recent version of a living history passed down since time immemorial.

This body-to-body is the very substance of Joan Dularge.

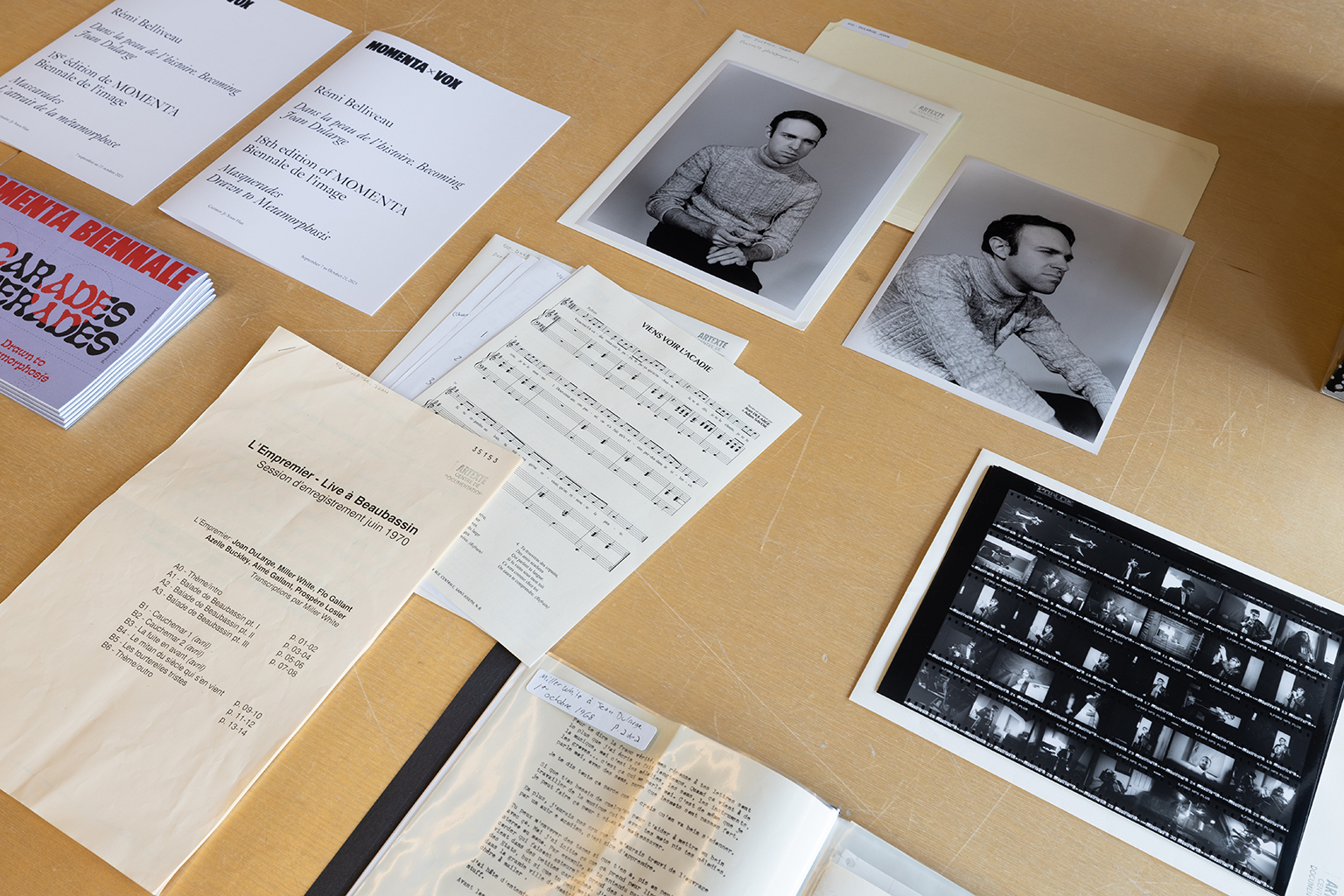

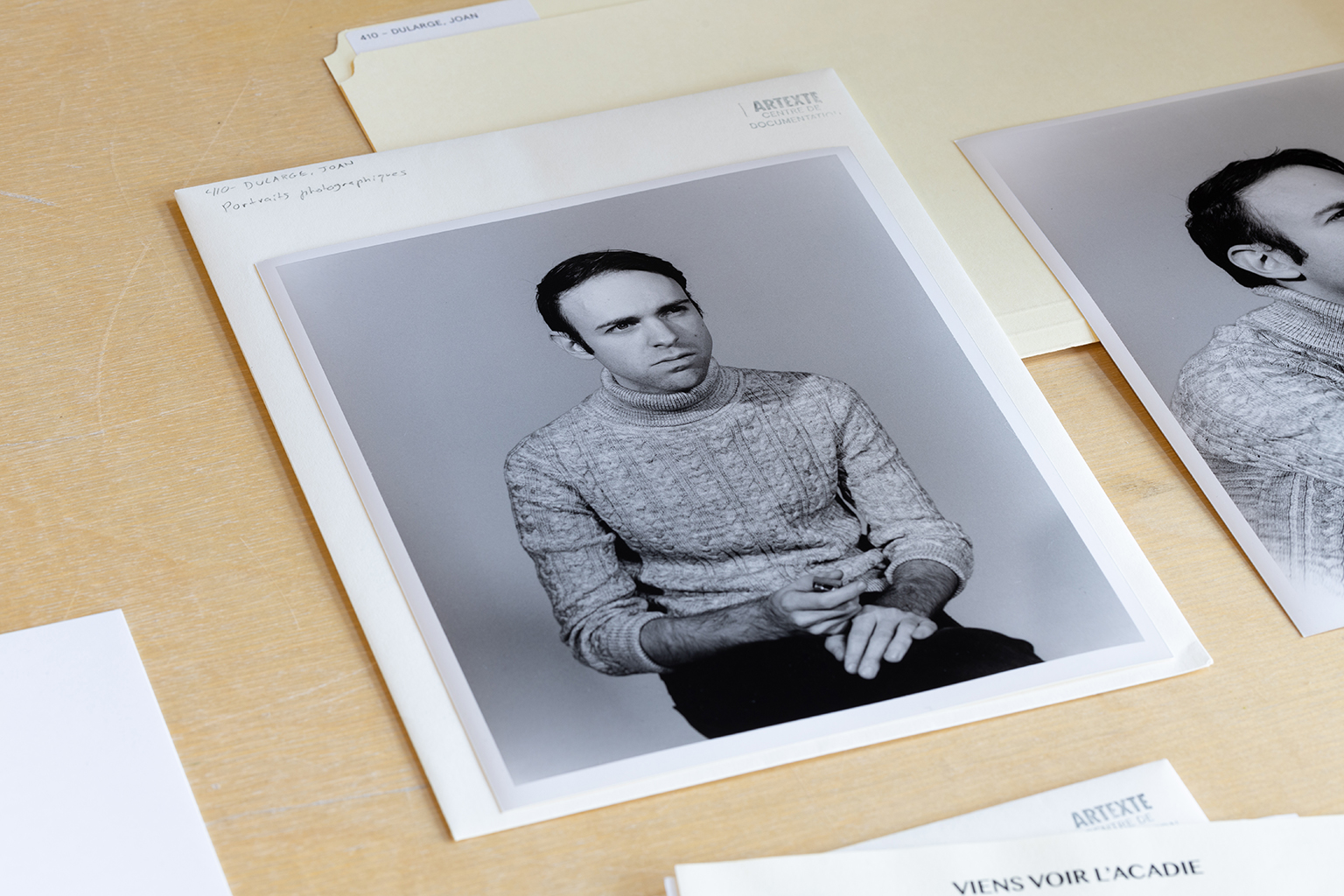

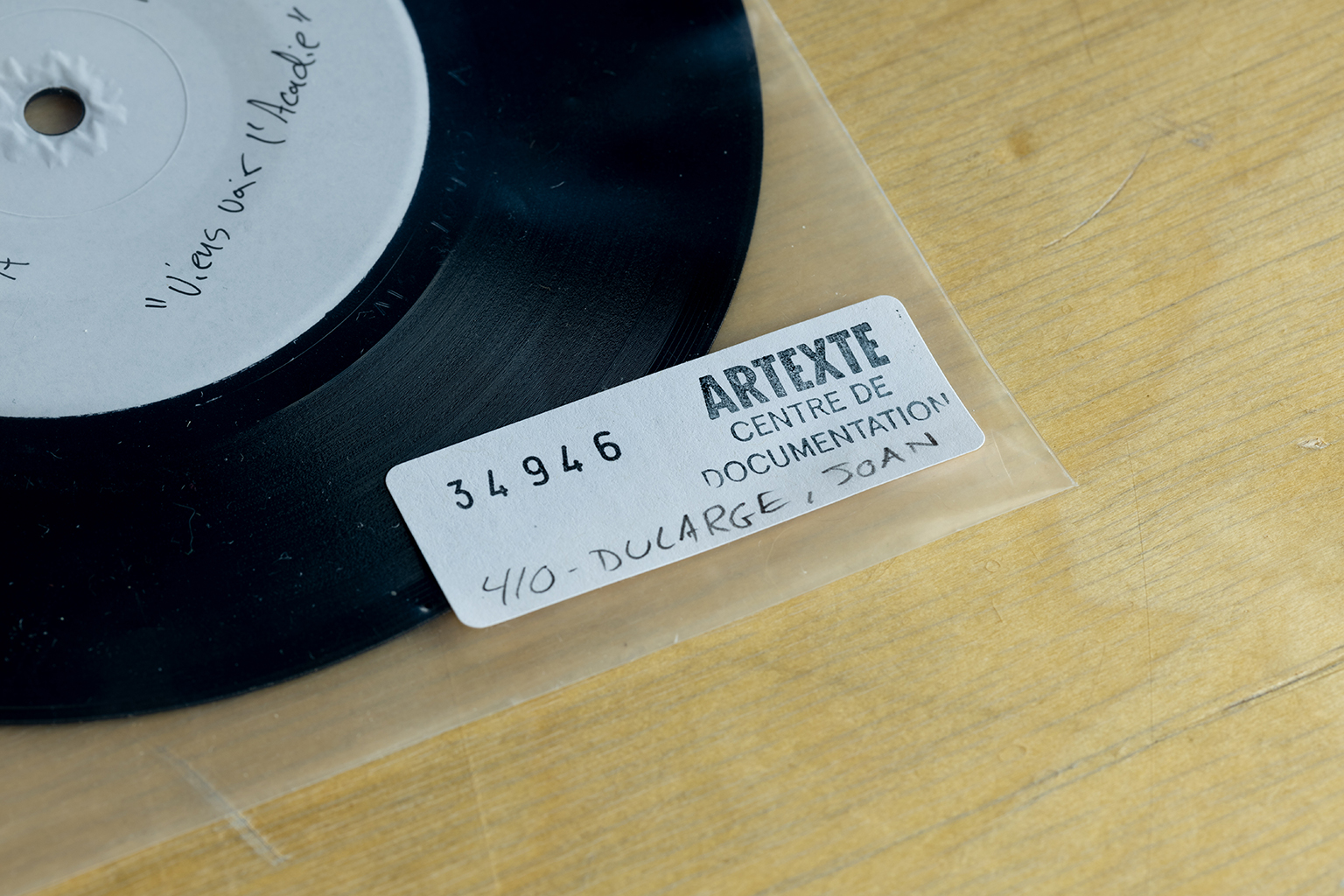

While Joan is indeed made up of material remains that I have sporadically provided them with since the fall of 2018—films, press photos, musical scores, vinyl records, a synthesizer, etc.—, their substance is only produced when living bodies like my own (but especially bodies other than my own) activate Joan’s archival system and thus produce memories in the flesh. These bodies are varied. Some of them act intentionally, others unintentionally. Those bodies that participate deliberately in this process are confronted with a choice: “Do I accept the objective logic of the archive, and thus the fictional nature of Joan Dularge? Or do I try and make Joan exist in an economy of body-to-body transmission activated and maintained primarily by the artist Rémi Belliveau?” Through the objective lens of the archive, the second option is in effect a falsehood: me and my collaborators are simply liars.

The politics of this lie are just as variable as the body that lies. Over the years, Joan has been maintained via media- and institution-based tricks acquiesced to by many an actor (artist and non-artists) working within these increasingly formal structures, including Artexte. In only five years, Joan’s immaterial body, supported by their allies, has gone from being messy and disruptive to a fairly stable and consistent entity.

A Chronology of Falsehoods

Joan first appeared in print media on September 28, 2020, in a Montréal Campus interview entitled Une exposition au timbre de la musique acadienne. At my request, Joan is described by journalist Aurélie Moulun as a historical figure “now gone from collective memory”. This was to be Joan’s media premiere, and indeed their mnemonic birth. A few months later, the editors of Canadian Art published my first article on the history of the Acadian rock music scene, where I included Joan among a selection of four genuinely forgotten Acadian bands and solo artists. The following year, I reworked Lost Classics of Acadian Disco and Rock ’n’ Roll in French as Hier semble si loin, and lengthened it to include nine groups and artists. This version of the text appeared as a 76-page book, numbered 35 in the carnets series published by Galerie de l’UQAM.

Prior to Artexte’s involvement in Joan’s career, the public availability of documents pertaining to their work was uneven and necessarily occasional, as it was largely restricted to art galleries—the acting custodians of these documents for the duration of an exhibition. Among these, the 2021 Sobey Art Award was notable for the infiltration of several Joan-related facts into administrative paperwork submitted to the National Gallery of Canada. As such, this was to be Joan’s first entry into a more stable and long-term institutional context, but, for the moment, sans collaborators on the inside.

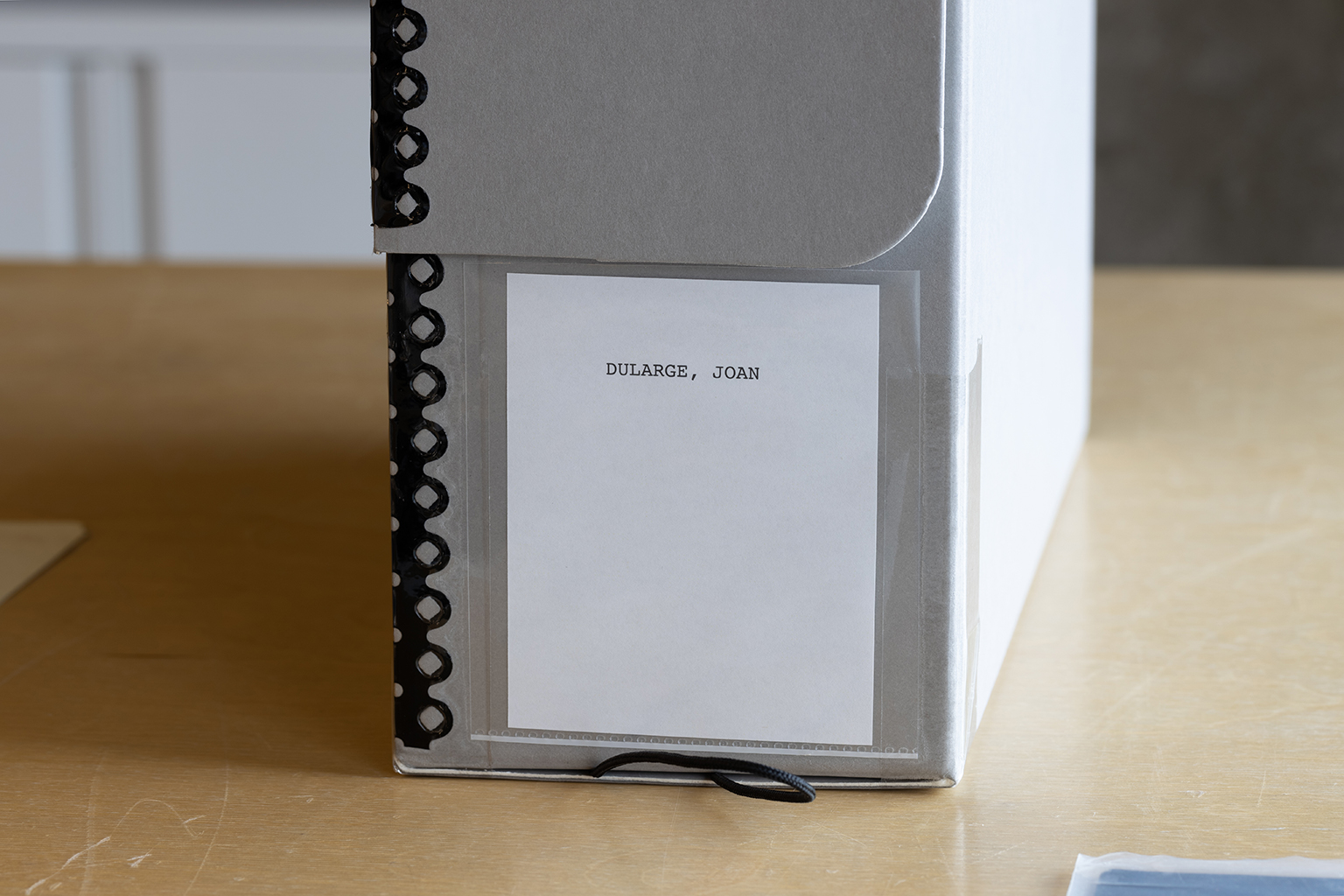

Indeed, it would take the arrival of the Artexte team (notably Mojeanne Behzadi, Manon Tourigny, and Jonathan Lachance), as well as the curators of MOMENTA 2023 (Ji-Yoon Han and Maude Hénaire) for a concerted effort of institutional mnemonic production to take shape around Joan Dularge. In acquiring the archives of Joan Dularge not as those of an alter ego of Rémi Belliveau, but rather as those of Joan Dularge themself, Artexte laid an important institutional cornerstone for all Dulargian fictions to come. Henceforth, detractors of Joan Dularge will have to contend with the fact that an institution like Artexte considers Joan Dularge to be an artist in their own right, deserving of a bona fide artist file in their collection.

Whether the Artexte employees believe the fiction or not, the archive is now able to interpret this reality autonomously, by following its own information management criteria. The archive is indeed now free to innocently transmit Joan’s story to other institutional entities and thus para-cite new, and possibly even more favourable points of entry. This was recently the case during preparations for the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec’s 2025 Prix en art actuel, when the Musée borrowed one of Joan’s musical scores from the Artexte collection (document no. 35153). In the administrative ritual of the inter-institutional loan, body-to-body transmission takes on a monumental dimension, as several bodies circulate several documents via several email accounts and several corridors to several offices where even more bodies wait to process them. This collaborative, hive-like activity amplifies the impact of bartered facts, especially when the documents in question carry the seal of approval of top management, as was the case with the loan agreements signed December 12, 2024 by Jean-Luc Murray, director general of the Musée.

“All of these things are intertwined and need sorted [sic].”

The exhibition at the MNBAQ was indeed a moment of high visibility for Joan, as well as for their band, l’Empremier—the Musée’s boutique being the first point of sale for their newly pressed vinyl album. Ironically, the circulation of the record in Quebec City piqued the interest of local obscure music aficionados, who quickly started investigating Dularge’s origins, and eventually “rectified” the “inaccurate” cataloguing information on Discogs, a platform popular with record collectors. A year earlier, user lxndress (a friend) had infiltrated the site and entered the original information on Joan Dularge, “in line with Dularge’s backstory”. However, a thread archived on Discogs forums (#1119063) contains a lively debate that ultimately led to the re-categorization of Joan (and their former male-coded name, Jean), as two recent alter egos of Rémi Belliveau, themselves based on an alter ego invented by Acadian singer Donat Lacroix circa 1974.

The motivation behind the Discogs debate is made clear in a comment from user teffjweedy, who notes the “intertwined” nature of these relationships, and expresses the need for them to be “sorted”. This reflex seems to stem from the idea that Joan could not possibly be an original figure, that they cannot share an origin story with another artist, and that their true origins should be clarified. Thus is designed the archive. And yet, the body-to-body transmissions that bring Joan into the present-day spring out of other trans Acadian musicians from the 1960s and 1970s who themselves have no name, no remains, but who clearly existed, and who we still carry with us today in our own bodies. Joan is authentic in the same way they are authentic, just as those musicians who preceded them were authentic, and so on. As Foucault says, “What is found at the historical beginning of things is not the inviolable identity of their origin; it is the dissension of other things. It is disparity.”[2]

Original becomes dissension becomes original becomes dissension becomes original: Joan Dularge reminds us that the binary constructs of reality/fiction, object/subject, present/past, and life/death simply can’t go the distance on a road paved with nuance. To be or not to be? Why not both? As Richard Schechner states:

“If the past was already self-different by virtue of being composed in restoration, then in the dizzying toss and tumble that always attends mimesis the fact that restoration renders an event different really only renders it the same as the original was: different.”[3]

Flesh of my flesh of my flesh, Joan Dularge tells us: “We are all citation.”

No sorting needed.