Let’s start at the beginning, with my first article about Digable Planets, and pass through the emotions of having been this young black kid into punk and indie in 1980, not into hip hop, moving to the East Village, and finally finding my flock of “young black Hegelians.” [1] Digable Planets, and other magicians of alterity like Tricky, could make us feel there was a third space. New spaces opened up for a whole alienated group of young black kids, with New York’s epicentre—which became mine—housing us as whatever we wished to be.

Preppy black kid, black punk kid, white-black kid, they would call us. Black kid not really into 1980s hip hop, black kid listening to Depeche Mode, black kid with Tears for Fears, crossing the frontier from our community into another and back again. Black kid drowning like the “flyboy in the buttermilk,” black kids in the East Village—very few of us. Black kids in the art scene—just three of us, in the 1980s. Yesteryear’s profound moments of isolated pain (still), for us flyboys and flygirls in the buttermilk are now celebrated as a renaissance. The “easy” moment of Afropunk black punks’ joy, as it seems now, was once a melancholic joyride drowned in the substances of the time. But alas, amidst that drowning was a wanderlust, a thriving for the unknown, without the digital spirit guides of algorithms—flyers, word of mouth, community. A real community. A black kid is floating between worlds. Basquiat as the patron saint of all of us “white-black” kids, and thus those infiltrators in the centre were wielding webs from this white world back into our own, and then back again and again and again, and again. We loved it, thrived in it. We danced in it. We were it. Many causalities and fatalities, but so much joy (fatalities like Harold Hunter, Lawrence Yitzhak Braithwaite, and Jean Michel). The signposts of that time—Daughters of the Dust (Julie Dash, Arthur Jafa), Chameleon Street (Douglas B. Street), Alma’s Rainbow (Ayoka Chenzira), John Keene’s Annotations, Trey Ellis’s Platitudes, Gina Dent’s edited book Black Popular Culture intoning notions of black pleasure and black joy, Danny Laferrière’s How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired—all the spirit guides of our in-between universes, aligned in the fight for alterity.

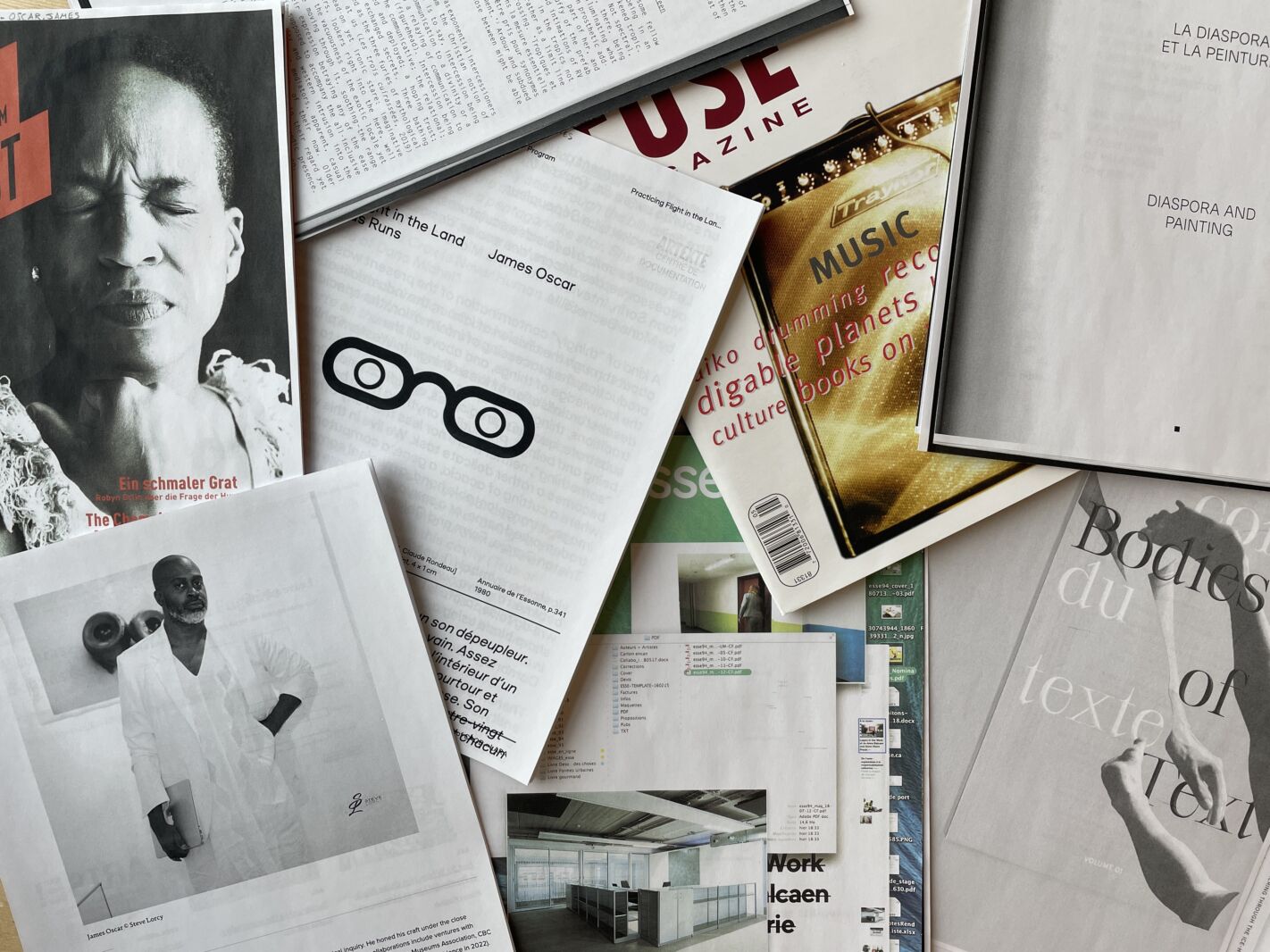

Enter Digable Planets (my first significant article) with their mustering of the in-between, singing at us and through us with what they called the “daisy age.” Finally, moments of exasperation beyond the melancholic—ultimately, for many of us black sheep—a scene, a place, a song, a way. They would be followed by Massive Attack, Tricky, etc., etc. But it would be in the careful embrace of the second article of my “career” that I could lean into the grace of present and future ancestors. Bottom, they were black as shit. And I sorely needed some black time. So, as the title made clear and following the name of their Grammy-winning record, the album established a new refutation of space and time regarding identity, at once offering a more complex manner of discussing that moment and its so-called “new black aesthetic.” As a precocious young cultural critic, I suggested that these artists were the “theorists” of the current moment, and that they were quick to ground their social and aesthetic engagement as “imaginative trespassers,” occupying a double-position of “skilled vision” but in no way vacillation in some wayward “in-between”:

See, we have had, in some ways, the privilege of solid parenting, but within the context of a strictly African American growing up and existence within urban areas of the country. You are, therefore, an observer of yourself and everything that goes on in your environment; you know what I’m saying. Take, for instance, gangster and gangster rap. We understand the mentality of it because we grew up around it, we also understand why it is popular and the social implications that supersede it—much more than the people who are doin’ it…. Just having that kind of knowledge is something that comes out in our music, being able to analyze a situation, but not like a sociologist from outside who goes in and does a case study but as a sociologist who has come out of it and is still in it and looking at it, and who still criticizes sometimes. [2]

This very positioning of the “alteritist” is, as they say, “who goes in … who has come out of it and is still in it and looking at it.” The second article planted, perhaps, one of the seeds of my future ventures of occupying such spaces of critical thinking. Another early tendency that I would solicit, one that would continue throughout my work and resurface in my very recent interest (since 2019) in the notion of “atmospheres”/“ambiances,” here evoked in proposing to Ishmael (from Digable Planets) that what caught my attention in their album was the “form,” or, as I put it, the “vibe.” Ishmael made it plain, saying that when we talk about a “vibe,” “it comes from knowing and feeling what the fuck you are talking about or what music you are putting together … knowing what is naturally true.” It was a prescient sentiment within the context of that moment (1994), a moment that the great British visionary Alan Moore would cite as a break in contemporary life and culture: with the entrance of a vibrant, global commercial regime in music, etc., with the advent of Britpop and, elsewhere, with the spiral into a new form of music commercialism and an ever-growing commoditization of everyday life.

These groundings in community, outlook, and rapport with a particular vision cited a striking similarity, during the 1990s, to the tendency of troves of black creatives adopting a kind of “black hippie” stance in reaction to the musical group De La Soul’s call for a “Daisy Age.” Knowledge would suggest that this understanding of De La Soul was obfuscated through the commercialized lens of their representation. Ishmael went further, stating: “that’s the difference between the people who said it and the people who reacted to it.” That elliptical range of confounding mere style with revolution [3] is a misunderstanding, one that has increased with the commodity fetishization of urban cultures, a process that’s been in hyperdrive since 1994 until today. From the beginning of my thirty-one-year journey, during which criticality was launched within and outside my community, in this first article and public engagement, it was with Digable Planets that I found some of my first “groundings with my brothers” [4] and sisters, and learned, early, how to refute any premade space and time imposed on me:

Well, it’s basically not so much a refuting space and then creating a new space, it’s like breaking down any walls around any type of space at all, so that you never feel like there’s never someplace you can’t go…. So Uncle Sam showed us all this space as Black people; the space he showed us was a little box, you know, whether it was your apartment, or your building, or your neighbourhood, it wasn’t enough space to feel like you had room to work in. So that’s why we said, “we refuted it.” We told him: “ghetto was the aim; let go of my brain.” It’s like: “let me go”; that’s what that’s all about—making space everywhere at all times, whatever times. [5]

That first extensive article, which I wrote so long ago, is still me today. Those early days of black alternative thinking in New York, Toronto, London, and Paris—how did those moments shape my whole career for me? Do black indie kids today realize that back in the day, wearing leather pants, for a black boy, meant physical threats on your life? Today, I stay attuned to the community and critique, at once, its ascensions and challenges. Thus, I have shaped a whole career of critical thinking, beyond the veil of the text into the lairs of everyday life. I recently wore the leather pants again—a kind of beautiful moment of black ascension: myself, still with my vigilance. This beautiful moment, for me, of interviewing Digable Plants, moving to New York, and finding my flock and its coterminous 1990s global black moment—a moment that seemed to have lost its ground—now raises its head again, almost thirty years later. [6]